This is the seventh edition of The Polycrisis newsletter, written by Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox.

The Year of the Tiger is over. In the new year of the Rabbit, diplomats from around the globe—the US, China, Russia, and most recently IMF leadership—are descending on Africa.

Last week, China’s new Foreign Minister Qin Gang kicked off a series of visits from top statesmen with visits to Ethiopia, Egypt, Gabon, Angola, and Benin. After meeting with her Chinese counterpart Liu He in Switzerland to discuss debt and crisis management, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen went on to Senegal, Zambia, and South Africa. On Monday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov was in South Africa, with later stops to be made in Botswana and Angola. He plans to return in February to visit Tunisia, Mauritania, Algeria and Morocco. Meanwhile, IMF’s director Kristalina Georgieva is on her way from Zambia to Rwanda.

“Our engagement is not transactional, for show, or for the short-term,” Yellen told a group of women entrepreneurs in Dakar in a speech last Friday that set the tone for her ten-day trip. “The United States is here as a partner to help Africa realize its massive economic potential.”

Notwithstanding the diplomatic pleasantries, Yellen came to Africa in mask-off mode. Even as she courted deeper partnership, Treasury Secretary Yellen painted a stark picture of the paths facing the continent. Each of Africa’s huge assets—especially its youthful working population and potential for growth—is Janus-faced, she suggested. Without adequate resources for development, the working-age population is a tinderbox liable to devolve into unrest and conflict. “Demographics is not destiny,” she warned. “Africa’s demographic momentum can propel economic growth if, and only if, adequate investments are made.”

To make those investments, the US is positioning itself as the high-road alternative to Russia and China, which are scouring the continent for minerals and arms deals. The barely-concealed subtext of Yellen’s geo-economic speech concerned not just the level but the origin of those investments. “Countries need to be wary of shiny deals that may be opaque,” she said, which “can leave countries with a legacy of debt, diverted resources, and environmental destruction.”

Europe has also escalated its ambitions to secure gas and transition metals—goals that will involve tighter alliances with Africa. In a Monday speech in Germany, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde warned that mineral demand from clean energy technologies could quadruple by 2040. “With the security of supply for critical inputs no longer guaranteed,” Lagarde said, “we are likely to see a new ‘scramble for resources.’”

The new US bullishness on African growth—always paired with sharp warnings about accepting investment from the wrong parts of the world—is in keeping with the gritted-teeth optimism of Biden’s December US-Africa Leaders summit.

At the meeting, African leaders sought support for Agenda 2063, the African Union’s long-term development agenda, and discussed the future of the African Growth and Opportunity Act, a trade program that provides some African countries duty-free access to the US in exchange for domestic reforms. The legislation expires in 2025. “From where I sit, the survival of AGOA will largely depend on changes to ensure more trade balance,” one African economist told Semafor.

American officials at the summit emphasized Africa’s potential for astronomical growth. Yet the US’s investment position is dramatically underweight Africa. Despite lawmakers seeing the continent as an essential player in the next century, and key to reviving sluggish aggregate demand, Biden plans to invest just $55 billion over the next three years. That is neck-and-neck with the commitments of other major countries, including much poorer ones. China has pledged $40 billion by 2025 and India expects investment to rise to $150 billion by 2030.

Meanwhile, China has been scaling down its overseas development finance, as Kevin Gallagher’s Global Development Policy Center has shown in a new report, “Small Is Beautiful,” on Beijing’s more selective approach to loans with smaller geographic and environmental footprints. But China’s 2008–2021 lending on the continent still rivals that of the World Bank. The question remains: why isn’t the US putting up the capital to back its official assessment of African potential?

Debt cancellation or “extend and pretend”

Even with substantial commitments of trade and aid, Africa enters the next decade of growth dragging a mountain of debt, estimated at $645 billion. On this front, Yellen has by most accounts been playing a genuinely constructive role. The gnarly task is to corral private sector and Chinese creditors into accepting debt haircuts.

China has been adamant that multilateral development banks, as well as private creditors like BlackRock, which is the largest owner of Zambian bonds, accept losses too. After a December trip to China, Georgieva returned, emphasizing a notion that she said is broadly shared by the Chinese public and officials: China will try to offer support, “but also, they expect to be paid back because [China] is a developing country.”

At G20 talks next month in India, creditors will attempt to move ahead on restructuring. There are some signs of a thaw in negotiations. But a debt restructuring is like a Mexican standoff: Everyone’s interests are opposed. China has raised potentially intractable objections. Bondholders want to minimize losses. Bilateral lenders want to put off the decision indefinitely. The IMF wants stability for the next 3-7 year program window. And debtor governments mostly just want to survive until the next election.

Africa’s ambitions depend on clearing away their debts. US and EU policymakers are now fixated on the climate crisis as a “threat multiplier” in emerging markets, emphasizing the havoc wreaked by drought and extreme weather. But physical threats are only part of the story. Africa will experience climate change as a debt crisis sooner and more pervasively than the continent will experience accelerating water stress and drought-related hazards. Interest payments are already eating into an unsustainable share of government revenue.

Meanwhile, if the debt overhang isn’t addressed, none of the things that the rich world wants from Africa will materialize. Creditor-enforced austerity would throttle Africa’s growth and green hydrogen developmentalist dreams.

The risks of a new Cold War

“I spend a lot of time in countries all over Africa, and they’re like, ‘Eh, we wouldn’t mind a little more globalization, actually.’” So said Bono in a recent interview with the New York Times. Perhaps the celebrity singer-philanthropist was channeling the great Keynesian economist Joan Robinson, who quipped that “the only thing worse than being exploited by capitalism is not being exploited by capitalism.”

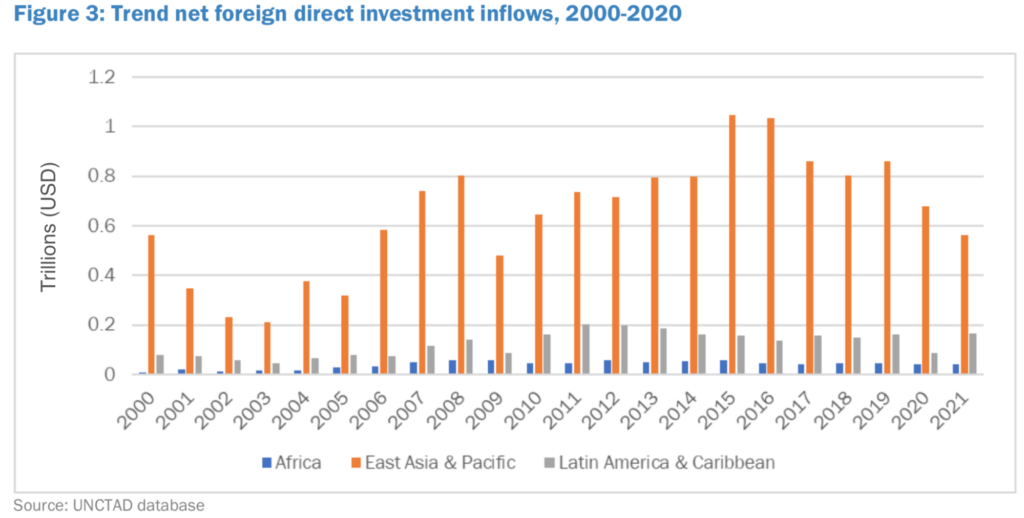

Over the course of the last few decades, a prominent story has been the takeoff of Asian growth against a backdrop of premature deindustrialization in Africa. Development depends on foreign direct investment and the technology transfer that can and should accompany it. FDI inflows to developing Asia totalled $476 billion in 2020, compared with just $38 billion for Africa. It is a travesty, as Hippolyte Fofack the director of African Export-Import bank points out, that Canada got more FDI in 2020 than fifty-four African countries put together.

The crucial question for development is not whether industrializing countries should plug into world trade, but how. The greatest risk to African development in the current climate is not North America and Europe scrambling for resources, but rather closing up their markets and cutting off FDI under the cover of new “onshoring” policies. The threat is real, since the US has hollowed out the political coalitions that once legitimized open trade.

At Davos, Georgieva cited IMF’s staff analysis to warn “geo-economic fragmentation” could cut GDP by 12 percent. How? By forcing countries to sever links, the new Cold War is going to hurt trade, migration, capital flows, and technology diffusion. That fear is perhaps why twenty-six African countries chose non-alignment.

Filed Under