Kishida’s New Capitalism

Comments Off on Kishida’s New CapitalismIn September 2021, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida was elected on an ambitious platform called “New Form of Capitalism.” As leader of the Liberal Democratic Party, he promised to achieve a new and better economic system where economic growth and income distribution form a virtuous cycle. The Japanese government has presented several plans to promote this new capitalism, but the Japanese people remain dissatisfied with the current economic reality. Despite the Japanese stock market soaring and the Nikkei index briefly surpassing levels only seen during the bubble period about 34 years before, economic growth has been stagnating since mid-2023. Kishida’s approval has steadily declined, dropping to 25 percent in February 2024 from over 50 percent in early 2022.

Kishida’s government is not the first to promise an innovative approach to economic management. In 2013, Shinzo Abe committed to reigniting Japanese economic growth through an expansionary monetary policy. But despite all of the tinkerings of Abenomics and the current Kishida plan, wage growth remains stagnant. Behind the policy innovations and campaign promises, a glaring development is hampering long term wage growth: the enduring decline in the bargaining power of workers. Any successful transformation of the Japanese economy thus ought to prioritize the structural power imbalances that plague sustainable and equitable economic growth.

Achievements and limitations of Abenomics

Shinzo Abe gained international fame through Abenomics, an economic strategy that integrated quantitative and qualitative easing, a flexible fiscal policy, and deregulatory structural reforms. Abenomics was designed to end the deflationary cycle and stimulate the Japanese economy through a reflationist approach. One of its key components was the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) purchase of long-term Japanese government bonds in order to induce liquidity. In April of 2013, the BOJ declared its intention to double the monetary base and achieve a 2 percent inflation target within two years. In 2016, it implemented a negative interest rate policy and yield curve control (YCC), directly controlling long-term government bond rates. Due to this expansionary and unconventional monetary policy, the BOJ’s holding of government bonds surged from 11.6 percent in March 2013, before Abenomics, to approximately 53.9 percent in September 2023.

In retrospect, Abenomics exhibited both successes and failures. While it effectively generated jobs and ended deflation, it fell short on wage and national income growth. Ultimately, it generated a slight economic recovery accompanied by increased employment and a tighter labor market. The Japanese yen depreciated due to quantitative easing, which resulted in increased exports, corporate profits, and a rise in the stock market index. The government debt to GDP ratio stabilized thanks to the strong control of interest rates by the BOJ, but the 2 percent inflation target was never realized despite overcoming deflation. Crucially, real wages increased only for two years between 2013 and 2020, and private consumption growth stagnated though there was a recovery of corporate investment. During the second phase of Abenomics, known as “Japan’s Plan for the Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens,” the Japanese government introduced more progressive reform measures. Beginning in 2016, it made concerted efforts to support irregular workers who faced discrimination in the labor market and to reduce excessively long working hours in Japan, as part of its revised labor reform agenda, known as Hatarakikata Kaikaku (“Work Style Reform”). Additionally, the government presented plans to increase social welfare provisions for child care assistance and support for the elderly. In order to raise the labor supply, promote domestic demand, and thereby stimulate economic growth, natalist policies have aimed to stabilize Japan’s population at 100 million by 2060.

Abenomics emphasized the importance of wage growth, and tried to establish a virtuous cycle of more egalitarian income distribution through stimulating domestic demand. Nevertheless, wage growth remained stagnant. According to a report by the Japanese government using OECD data, the level of real wage per worker increased by 41 percent in the US and by 34 percent in Germany and France, but it increased only by 5 percent in Japan between 1991 and 2019. Japan has suffered from an excess saving problem—a major sign of macroeconomic imbalance, as corporate saving from profits has been much larger than investment, more serious than other advanced countries.

Abenomics clearly failed to halt the long and continuous stagnation of wage growth—in fact, real wages in 2019 were even lower than those in 2013, while corporate profit increased significantly. Abe’s tax reforms further favored capital over workers: between 2013 and 2016, the government cut the effective corporate tax rate from 37 percent to about 30 percent, while raising the consumption tax rate from 5 percent to 10 percent between 2013 and 2019.

It is no wonder that economic recovery proceeded slowly. Private consumption, the largest component of GDP in Japan, recorded positive growth only in 2013, 2017, and 2018, while GDP growth was positive from 2013 to 2018. The Japanese economy entered a recession, experiencing negative growth in 2019 even before the Covid-19 crisis. In response to the pandemic, the government implemented large-scale fiscal stimulus packages, but the recovery was still slower compared to other advanced countries.

Kishida’s plan for New Capitalism

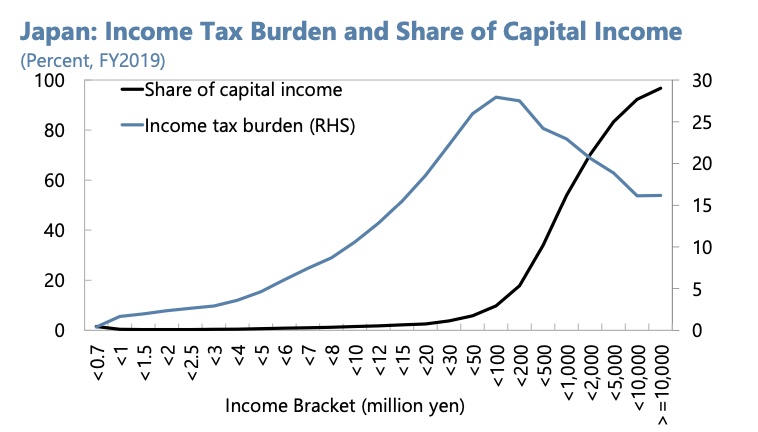

The weaknesses of Abenomics formed the backdrop to Kishida’s energetic campaign. Kishida’s New Form of Capitalism notion specifically emphasized the need for wage growth among vulnerable workers. During his campaign for leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), he argued for increasing the wages of workers in healthcare, childcare, care for the elderly, and those working in subcontractor companies. Given the absence of an heir to Abe’s platform, he was able to capitalize on these promises to enter government. He also presented a plan to raise the capital gains tax, which stands at a flat rate of only 20 percent compared to a 55 percent income tax for the highest bracket. The gap between the two tax rates means that the real tax burden falls after income exceeds about 100 million yen in Japan, referred to as the “100 million yen barrier,” as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1. Income tax burden in Japan

But the plan for raising the capital gains tax was retracted due to resistance and a fall in the stock market. In 2021, the Nikkei 225 fell for 11 consecutive days after Kishida announced his plan on September 30, and he canceled it on October 11. Later in 2023, the Japanese government introduced a limited hike of the capital gains tax up to 22.5 percent for only the super-rich who earn more than 3 billion yen.

Though Kishida was not very successful in raising the capital gains tax, New Capitalism persisted. In his first speech as Prime Minister, he stressed that there is no growth without redistribution. Kishida established the Council of New Form of Capitalism Realization under the PM’s office shortly after his election. The council, chaired by Kishida, began organizing regular meetings consisting of government officials, the representatives of companies, workers, and specialists. At the meeting in November 2021, the government announced its reformed agenda in a document called “Urgent Suggestions for a New Form of Capitalism.” The government underscored the creation of sustainable stakeholder capitalism in which growth and distribution form a virtuous cycle. The plan includes a growth strategy encompassing green economic transformation. The distribution strategy covers wage growth for vulnerable workers, the reduction of the wage gap, promotion of investment in human capital, and support for companies to raise wages. In December 2021, another plan by the government was presented for the government to supervise fair trade between large firms and small subcontractor firms so that increases in cost due to external shocks could be smoothly transferred to the subcontract prices.

In June 2022, the Japanese government presented the ‘Grand Design and Action Plan for a New Form of Capitalism.’ The document presented New Capitalism as the next stage in a natural evolution from laissez-faire to the welfare state, and then to neoliberalism. New Capitalism is the system in which the market and the state together strive to realize people’s happiness by addressing inequality and climate change. It argues that fair distribution of the fruits of growth is an investment in sustainable growth, and Japan should make efforts for wage growth, fair trade, and better education. In particular, the government announced that it would make strategic investments in human capital, science and technology, startups, and transformation of green technology and digital technology. Specifically, investment in human capital and distribution includes several plans for wage growth and worker training, such as the government subsidy for companies to raise wages and the appropriate setting of delivery prices by subcontractor firms. Other plans such as doubling asset income and the promotion of startup companies were announced in November 2022. In May 2023, the government presented a three-pronged plan for labor market reform to improve workers’ skills and introduce job-based wages. It is notable that the Japanese government, specifically the Council of New Form of Capitalism Realization, has been updating and following up the plan continuously.

In general, the plan for New Capitalism was broadly in line with inclusive growth strategies suggested by international organizations after the global financial crisis, while also following the main tenet of the second phase of Abenomics. It is also consistent with the revival of industrial policy and the modern supply-side economics characteristic of the Biden administration.

Recent economic growth and wage growth in Japan

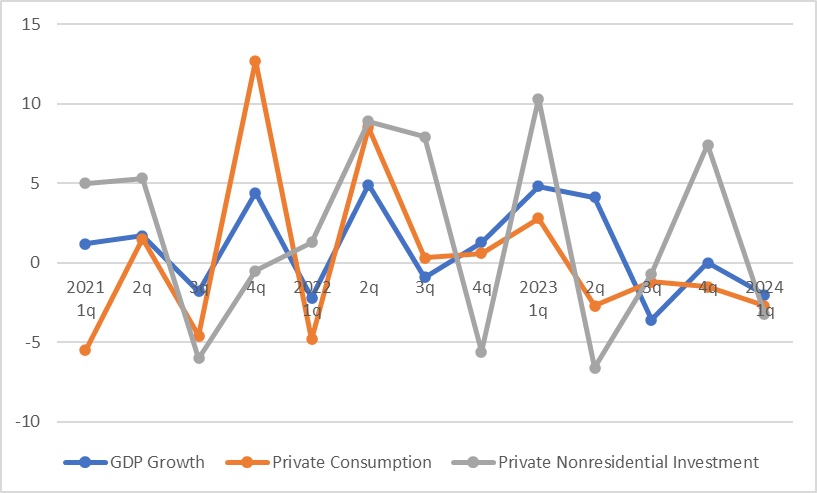

Kishida’s New Capitalism faces significant challenges. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, the government has sought to boost, through fiscal stimulus, programs meant to support households against inflation. But the economic recovery in Japan has been relatively slow, especially compared to that of the US. The fiscal stimulus Japan disbursed in response to the pandemic amounted to 16.7 percent of GDP by September 2021, smaller than 25.5 percent in the US. The growth of private consumption has been particularly weak, recording negative figures since the second quarter of 2023, along with stagnant household income and wages in the recent period. Although the real GDP growth rate in 2023 was 1.9 percent, higher than before, the Japanese economy suffered from negative growth in the third quarter and zero growth in the fourth quarter of 2023. The economy stagnated even further with the GDP growth rate at -2 percent in the first quarter of 2024.

Figure 2. Economic growth of real GDP and components in Japan (%)

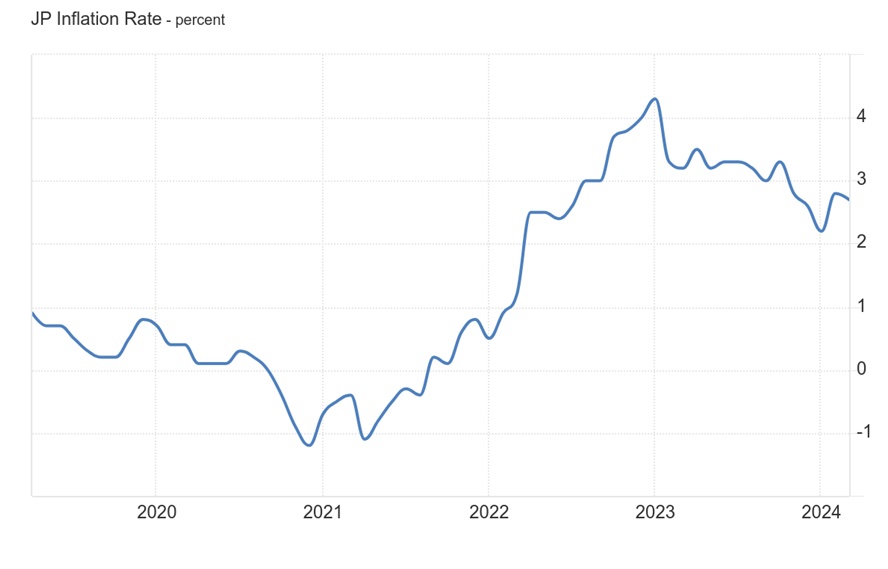

Inflation finally returned to Japan, peaking in late 2022, but the BOJ did not rejoice. Inflation was not associated with the stimulation of domestic demand backed by wage growth, as expected by the BOJ and the government, but with an external shock; the yen’s depreciation. The BOJ had continued the negative interest rate policy and the YCC, though with some tweaks to allow the long-term bond rate to rise gradually. This led to a large gap between the interest rates in the US and Japan because the US Fed hiked the interest rate rapidly in 2022. Hence the Japanese currency’s significant depreciation, from 110 yen per one dollar in January to 150 yen in October, which stands at about 156 yen as of May 2024. Together with the increases in energy and food prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the depreciation of yen increased consumer price index inflation to even higher than 4 percent in late 2022, though it has slowed to 2.7 percent as of March 2024, as Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3. Consumer Price Index Inflation Rate in Japan (%)

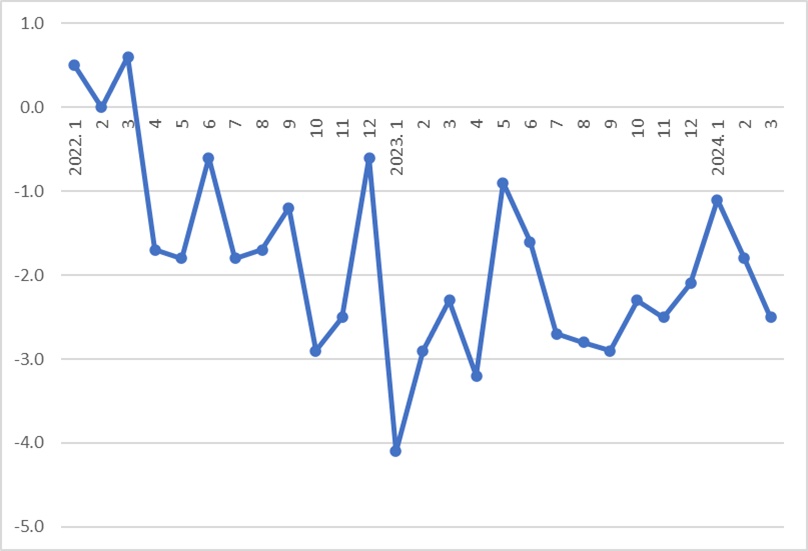

The problem is that nominal wage growth was much lower than inflation. The real wage growth has been negative consecutively for 24 months since April 2022, as Figure 4 illustrates, although the fall became smaller in January 2024. This is the opposite of what was expected by the New Capitalism plan.

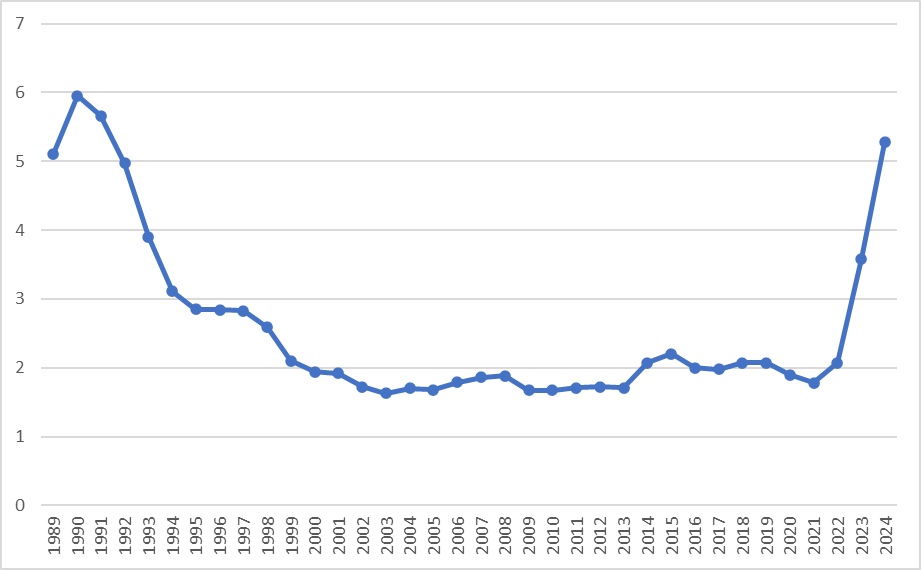

Kishida’s government has been active and enthusiastic about calling for wage increases, and large companies have responded positively in the recent period. Fast Retailing Co., well known for its primary subsidiary, Uniqlo, raised wages by 40 percent in 2023 and other companies followed suit. Even the Japanese business federation Keidanren argued that the wage increase is the responsibility of companies. Companies that engage in wage negotiations with labor unions each spring, called Shuntō, saw an average wage growth of 3.6 percent in 2023, much higher than before, as Figure 5 demonstrates.

Wage increases are expected to be even higher in 2024. According to the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, known as Rengō, the first release of spring wage negotiations shows that wages rose by 5.3 percent, the highest after 1991. Just after this, the BOJ increased the interest rate, for the first time since 2007, ending the negative rate policy and yield curve control, because it assessed that the Japanese economy can finally achieve healthy inflation along with the wage increase and the expansion of aggregate demand. Contrary to the US, where the wage-price spiral was viewed with enormous concern, the BOJ has actively pursued this positive spiral since the implementation of Abenomics.

Figure 5. The wage increase from spring wage negotiation (%)

Not macroeconomics, but political economy of wage growth

The rapid increase in wages due to cooperative bargaining and changes in monetary policy are surely good news, a sign of reflation in the Japanese economy after about 30 years. However, it remains to be seen whether Japan is actually on the verge of ending its long-run economic stagnation. While large companies with labor unions have increased wages, many small and medium companies have little room to do the same, significantly contributing to the stagnation of wage growth. Moreover, the role of trade unions that would be indispensable to the wage increase is very limited. Thus, the overall nominal wage growth was only 1.2 percent in 2023, much lower than the result of wage negotiation between companies and labor unions. This is in stark contrast to the recent surge in the Japanese stock market. The Nikkei 225 index increased up to higher than 40,000 points in late March 2024, higher than the peak of the bubble in December 1989. The surge was mainly associated with the increase in corporate profits, the government’s effort to support the stock market through corporate governance reform, and the inflow of foreign investment. However, the share of people who invest in the stock market in Japan was just 12 percent of the total population as of 2022, while the share of people without any savings was about 27 percent.

There is a growing recognition of the urgency of wage growth across Japanese society. A recent report by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare argues that a 1 percent increase in wages can lead to an increase in consumption and growth, raising production by 0.22 percent and creating an additional 160 thousand jobs. But after a decade of policy experimentation, it’s increasingly clear that this sort of wage growth depends on recalibrating the balance of power within the real economy. Japan’s unionization rate has continued to decline for several decades, alongside an increase in the share of irregular workers. The unionization rate fell from 30.8 percent in 1980 to 21.5 percent in 2000, and further to 16.5 percent in 2022, with the rate of union membership for part-time workers being only 8.5 percent in 2022. The share of irregular workers in the total workforce continued to rise from about 20 percent in 1990 to about 37 percent in 2022.

Japanese trade unions are formed at the corporate, rather than the industrial level. Individual unions are typically segmented and take decentralized actions, possessing limited bargaining power. In recent years, Japanese unions have increasingly turned to cooperation with employers. In fact, there were only sixty-five strikes in 2022. Strikes had peaked at 9,581 in 1974 but fell sharply to 1,698 in 1990, to 129 in 2005, and dropped to less than a hundred after 2008.

The strike by workers in the Seibu department store in August 2023, the first strike of labor unions in department stores in sixty-one years, caught Japanese society by surprise. It is clear that not only social consensus but also the workers’ struggle to organize is essential to the wage increase in Japan. Moving forward, any plan toward a sustainable economic recovery must prioritize enhancing workers’ negotiating power and promoting unionization among irregular workers and workers in small firms. Without a fundamental change in the balance of power, nothing new will come of Kishida’s New Capitalism.