Democracy in Power: A History of Electrification in the United States

By Sandeep Vaheesan

University of Chicago Press, 2024

Electricity, it has become widely recognized, is the key to surviving the twenty-first century. Not only is it required for air-conditioning during worsening heatwaves, it also is one of the only ways we already know to produce large amounts of energy without necessarily pumping megatons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, worsening the global climate crisis. Using that energy effectively will involve widespread electrification of many end-use products, like automobiles and home heaters. At the same time, however, the United States is by far the world’s largest cumulative emitter of greenhouse gases, in large part because its electric power sector has itself historically been its largest polluter.

Solutions to the global climate puzzle therefore rest not only on expanding the use of electric power, but also on making electricity generation in the US cleaner.

Sandeep Vaheesan’s timely new book, Democracy in Power: A History of Electrification in the United States, is written with all of this in mind. Vaheesan’s aim is to transform how we think about governance in the power sector, so that the movement toward decarbonized electricity is more democratic—which for Vaheesan means less corporate and shareholder dominance and more public accountability—than it has been thus far in the US. This is by no means an easy project in the twenty-first century. Decarbonization has so far advanced as largely a privately controlled market phenomenon. Its areas of greatest progress in the US have been the growth of natural gas from fracking (cleaner than coal), and of renewables investments in wholesale power markets (like California and Texas).

Democracy has played little overt role in either development. That fact reveals the importance of this book and its thesis that decisions over where, how, and for whom we generate and distribute electricity are inextricable from broader controversies over how we should govern ourselves politically.

Governing the grid

As a reader of Vaheesan’s book will discover, governance of the US electric power sector is a subject of byzantine complexity. Not for nothing is the US power grid often called the world’s largest machine. It comprises three technical functions—generation, transmission, and distribution—and is governed at multiple and overlapping levels of government: federal, state, regional, and municipal. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (formerly the Federal Power Commission) and state-level utility commissions, whose powers can differ substantially, provide the federalist pillars of electric utility regulation. Then there are the eight transmission organizations—usually called Independent System Operators (ISOs) when they correspond loosely to one state or Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) when they cover many states. These non-profit entities, overseen by FERC, coordinate and monitor their members’ use and development of some (but not all) of the country’s interstate (and sometimes intrastate) grids.

Electric power companies take three main legal-organizational forms, differentiated by who owns or controls them: investor-owned (owned by their shareholders), cooperatives (owned by their customers), and “public power” organizations (owned by government bodies). In addition to the ISO and RTO industry association rules, government regulation of these companies differs by type: public power companies are exempt from utility commission rules, as are shareholder-owned “independent power producers”—the segment of the market that has shaped current trends in new fuels and technologies. Then there is the physical grid, the geographic circuit, which functions in practice as three distinct grids—East, West, and Texas—that don’t correspond to neat political borders, and within each occur commercial exchanges of interregional transmission.

Given this geographic and organizational complexity, Democracy in Power is a feat of explanation. Most historians of electrification in the US have chosen to limit their subject matter in one of three ways. Either they stop the story by the mid-twentieth century, pick one or two cities or regions, or focus on one main technical function. By organizing the book around legal forms, however, Vaheesan can zoom in and out of the local, regional, and national political conflicts that have shaped the evolution of the American electrostate across its century-and-a-half-long history.1

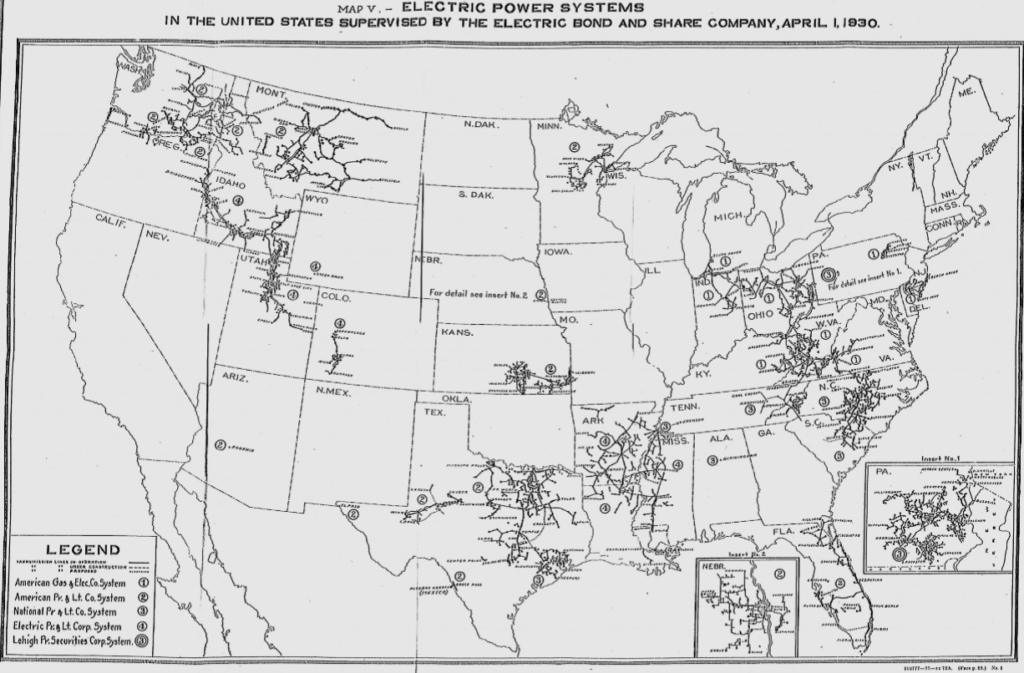

The book opens with a classically American foil: the investor-owned monopoly utilities and their holding companies. From the 1880s through the Progressive Era, monopoly regulation of electricity companies was traditionally the remit of municipalities and the states. Accordingly, utility executives, especially from the turn of the century onward, formed complex, multistate holding company structures to exploit the lack of federal regulation over interstate power sales and stock issuance. This allowed a small number of executives who owned the common stock in holding companies to control and earn large profits from many different operating companies at the expense of those companies, their other stockholders, and their customers. Utilities operated mainly in cities because most utilities and their holding companies claimed—wrongly, it turned out—that rural electrical demand was impossible to cultivate and electrifying rural areas would not be financially possible.

(Source: US Congress, Senate, Utility Corporations: Summary Report of the Federal Trade Commission, 70th Cong, 1st sess, 1935, p. 89.)

In opposition to the profit demands of investor-owned utilities and their reluctance to serve the rural market, Progressive reformers organized political campaigns to establish alternative organizations. Municipally owned utilities, rural electric cooperatives, and public utility districts began to fill the gaps in generation and distribution. By the 1920s, the federal government had also become directly involved in building and operating multipurpose hydroelectric dams, while the Federal Power Commission (FPC) began licensing non-Federal projects. Then Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected alongside a substantial Democratic-majority Congress during the nadir of the Great Depression. In what is perhaps the most well-covered episode in US electricity history, the federal government founded the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally owned electric utility corporation championed by Nebraska Senator George Norris that entered the power sector with the direct purpose of serving the underdeveloped Appalachian South. Meanwhile, with the Public Utility Holding Company Act Congress heavily curtailed the ability of corporate magnates to own and reap outsized rewards from numerous far-flung and physically unconnected utility operating companies.2 In the late 1930s, the Rural Electrification Administration began promoting rural electric cooperatives by offering them technical assistance and loans on more favorable terms than other types of utilities, filling out the assemblage of different power organizations dotting the country.

While much of this early history is well known, one of Vaheesan’s contributions is to show that the letter of the law, especially case law, had a significant effect on what utilities were permitted to do. One galvanizing issue was the rates charged to customers. For example, in a set of key legal precedents for state-level utility commissions, the Supreme Court allowed states to regulate businesses that put their property “to a use in which the public has an interest,” a phrase dating to the landmark 1877 case Munn v. Illinois that at first applied only to grain warehouses and railroads. In Smyth v. Ames in 1898, the Court ruled that regulated businesses had a constitutional right to a “fair return” on the “fair valuation” of their properties.3 This was the legal basis of the provisions of subsequent state utility commissions—36 of which were founded between 1907 and 1919—asserting the “just and reasonable” principle for the determination of prices charged to customers by regulated electric companies.

As state regulation took hold, the contest narrowed to the regulatory details. As Vaheesan explains, determining the fair valuation of property was often a cumbersome legal affair. The Court’s guidelines for valuation contained a laundry list of factors, including not only the original cost, but also the presumed market value of bonds and stock and the “probable earning capacity” of the property. Most utility commissions therefore interpreted fair value as “reproduction cost”—the presumed cost of replacing a power plant or transmission line determined by credentialed appraisers paid by utility corporations—rather than original cost. Holding companies exploited this interpretation to inflate the book value of operating company assets. Although both costs and rates generally decreased over the first few decades of the century for technological reasons, this practice had the effect of increasing regulated rates beyond what they otherwise would have been. Then, in Hope Natural Gas Co. v. Federal Power Commission in 1944, the Court gave more freedom to state commissions to determine which valuation methods to mandate, including simply original cost without other factors.

Ownership and use of today’s electric grid differs tremendously from the vertically integrated utility companies that early-twentieth century US democracy sought to control. The most significant change is also one of the most recent: the separation of transmission and distribution from markets in generation, market restructuring that accelerated in the era of Clinton and George W. Bush.

Restructuring power

Few books summarize the policy changes that led to restructuring so succinctly and comprehensively as Democracy in Power. Cost pressures for regulated rate increases—a profit squeeze—in the mid-twentieth century set the stage for this disaggregation of functions that defines the business today. From the early twentieth century until the late 1960s, generating efficiencies and economies of scale enabled (though by no means ensured) generous profits, despite a steady decline in regulated retail electricity prices. Improvements in the metallurgical construction of turbines, for example, meant the thermal efficiency and size of steam turbine-generators rose at a steady clip. By the late 1960s, the country had dammed most of its major rivers, while metallurgical improvements also plateaued. Construction and fuel costs began to rise.4 As all of these cost pressures rather abruptly stopped the industry’s ability to meet additional demand at low prices, policymakers at the state and federal level began to respond. Some state commissions, as Vaheesan details, began allowing utilities to include new kinds of costs, particularly “construction work in progress,” as part of the value determining current rates. For the first time in nearly half a century, utilities across the country during the Vietnam inflation began raising prices in real terms.

By allowing utilities to pass rising costs onto the public, however, state commissions tended to ignore the sources of the squeeze in profits from plateauing geographic and technological development. Additionally, the problem of rising costs was exacerbated by the Arab-Israeli conflict that quadrupled oil prices overnight in late 1973—costs utilities also passed on to customers. The US was unique among large, developed nations in generating nearly 20 percent of its electricity in this moment from fuel oil. The problem of oil—the control of prices and allocation of product at the wellhead, refinery, and filling station—therefore dominated the politics of energy throughout the 1970s. Even when the FPC, which became the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) during the creation of the Department of Energy in 1977, issued an Order standardizing the use of “construction work in progress” clauses by state utility commissions, it was oil pipelines more than electricity companies that commanded the center of public attention.

Accordingly, Congress did not begin seriously considering utility reforms until the Carter administration entered in 1977. Carter’s National Energy Plan favored conservation—a goal that extended beyond oil consumption to electricity production and pervaded the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) introduced in the House and Senate late that year. As is scrupulously detailed by the electric power historian Richard Hirsh, and related by Vaheesan, most public scrutiny over the bill centered on these conservation programs and other provisions in the bill that directed state commissions to consider alternative ways of pricing power. By the time Congress had passed PURPA after more than a year of debate and modification, however, little attention had been paid, even by utility lobbyists, to a small but ultimately significant section of the bill. Section 210, titled “Cogeneration and Small Power Production,” inaugurated a new category of power producers, collectively called “qualifying facilities,” exempt from traditional utility regulation. At the time, few utilities anticipated that alternative generating technologies from new entrants could yield energy efficiencies significant enough to offset rising fuel costs. While the power produced by these new kinds of companies—most of which was from “co-generators,” or industrial facilities that reuse waste heat to make electricity—brought only minor efficiency improvements and uncertain price relief, over subsequent decades they ultimately became a small but important segment of electricity generation. With “qualifying facilities” having gained a stable foothold, the overall landscape for the generation of electricity now looked slightly more like a competitive market. For the first time since the very early days of electric utilities, a separate category of power producers began competing directly with utilities to generate electricity.5

The more rapid growth of what are more commonly called “independent power producers”—so named for their independence from the public control exercised by state utility commissions—came later, during the 1990s and 2000s. The Energy Policy Act of 1992 traded tighter environmental standards for “deregulation,” creating a new class of “wholesale generators” exempt from the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935, allowing them to sell wholesale power at rates not subject to the “just and reasonable” standards of federal rate regulation. Then, in 1996, FERC issued a landmark Order mandating that transmission-line owners provide open, non-discriminatory access to all generators, whether private, public, or independent. As a result, many states began restructuring their power systems to separate transmission from generation; forcing vertically-integrated utilities to spin off their generating assets; and establishing, often together with other neighboring states, competitive wholesale markets in generation with marginal-cost pricing. This is the origin of today’s private regulatory system of clubby non-profit transmission organizations (RTOs and ISOs). Joining such organizations, FERC suggested, would not only ensure open-access transmission grids but also allow them to operate as the equivalent of wholesale market exchanges.

The precise way states and regions have restructured their power systems differs radically across the US. Consider the effects of different transmission organizations’ marketing rules on generating capacity. The RTO governing the Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland Interconnection (PJM, which includes much else besides those states) operates both a day-ahead and real-time spot market for electricity, and also a “capacity market”—an additional auction to compensate generators for power they may provide at some point in the future at a moment’s notice. Texas’s ISO, meanwhile, is said to have an “energy only” market, consisting of a day-ahead and real-time market, but no capacity market. These two transmission organizations have markedly different effects on the availability and carbon intensity of electricity. In 2019, PJM had over 30 percent more generating capacity than necessary to meet the peak electrical demand that year. (This is known as the “reserve margin,” which, to be considered safe according to historical convention, should be between 15 percent and 20 percent.) In Texas’s energy only market, meanwhile, the opposite problem prevails. In 2019, the reserve margin fell below 10 percent. In extreme cases, like that of Winter Storm Uri in 2021, a low reserve margin, though not a cause in itself, can severely exacerbate power outages. At the same time, it is ratepayers who foot the bill for extra reserve capacity. Since renewables don’t on their own provide what is referred to as “firm” power, and thus don’t qualify as on-demand, the reserve margin is also usually fossil-fueled.

Although these two regions are perhaps extreme examples along the spectrum of marketing rules across the nation’s seven transmission organizations, highlighting the differences between regions serves to remind policymakers and commentators alike that the finer details of these rules have large effects. Given how poorly much prominent political commentary on the US power sector today captures this fact, Vaheesan’s description of the tradeoffs of these different governing structures in different places in the US is a remarkable contribution.

Democracy’s birch rod

Democracy in Power is not just a history. It is also billed as a guide to our electrical future. In making his case for “public power for the entire country,” Vaheesan appropriates from the history of federal and municipal government-owned utilities, public utility districts, and rural electric cooperatives—companies that have usually existed at some distance from the regulations of utility commissions, due to the absence of shareholders from their controlling constituencies. This history is itself a second major scholarly contribution of the book. With it, he builds a normative political argument: public power is the model for Vaheesan’s program to restructure the entire power sector to be more accountable to the public and less dominated by investor-owned corporations and their shareholders. By far the most important plank of this program is the threat (and actuality) of government ownership, an institutional arrangement that thrived at the turn of the twentieth century and in the era of Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Before the advent of state utility commissions in the early twentieth century, the politics of electricity consisted mainly of devising effective means of forcing investor-owned companies to expand service to residential customers and lower their rates. During these formative years, the threat of municipal government takeover or the withholding of a utility franchise—the contract between a local government and a utility that gives it the legal right to operate—served this purpose.6 The TVA applied this approach—which Roosevelt once referred to as “a birch rod in the cupboard to be taken out and used only when the child gets beyond the point where mere scolding does no good”—at an expanded scale.7 New federal and state laws could reconstitute that birch rod today, Vaheesan recommends, by delegating greater eminent domain authorities to states and cities and providing them with more expansive charters that would allow them to organize new public corporations in the service of new goals, like decommissioning fossil-fuel plants and building out distributed solar and wind energy resources and battery storage. Vaheesan even draws lessons from the recent history of many public power organizations and rural electric cooperatives to specify what “true public utilities” would look like in terms of their board structure, functional purpose, and day-to-day activities, like disclosures and elections.

Other policy proposals are more far-reaching. The TVA’s most perseverant forebear, Senator George Norris of Nebraska, proposed during the New Deal the creation of seven regional power authorities, or “seven little TVAs,” which Vaheesan here revives dutifully. These would usurp the planning function of current transmission organizations and function as “yardsticks” (another term Roosevelt popularized) against which investor-owned utilities would then be measured—as still occurs to a limited extent with the TVA in the Southeast, the Hoover Dam and LA Department of Water and Power (LADWP) in the Southwest, the New York Power Authority (NYPA) in New York, and the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) in the Northwest. These proposals, and many more in the book, would depend on Congress.

Although Vaheesan’s ideas for reform are based on a rigorous historical recounting of electric-power politics, key questions remain. One rather important one is whether the technical and therefore economic features of power generating infrastructure needed for decarbonization—above all, solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries—present new and different challenges for institutional design. The vertically-integrated, investor-owned monopoly utility regulated by a state commission thrived in an era when coal, steam turbines, and their increasing economies of scale dominated the electricity mix. Large government-owned utilities—TVA, BPA, NYPA, LADWP, and municipal public utility districts of the Pacific Northwest—institutionalized a publicly owned version of this model around large, multipurpose hydroelectric dams. Few sites for such projects remain, although turbines could be added to many existing sites. Nuclear, the costly but carbon-free fuel that grew to 20 percent of the electricity mix from the late 1950s to the late 1980s, found the most success with vertically integrated companies, whether they were public like the TVA, or private like Commonwealth Edison and Duke Power. Because vertical integration proved useful for constructing nuclear power plants, the disintegration of power companies across much of the country creates significant uncertainties for new nuclear energy. To make matters more difficult for the public option, most municipal utilities (with the exception of Los Angeles) and rural cooperatives have historically generated much smaller amounts of electricity compared to what is needed in their locales for the task of decarbonization, since households have so far needed comparatively less electricity than commercial and industrial consumers.

Market decarbonization

In the years since deregulation and restructuring, a new set of dynamics has characterized the US electricity system. One defining feature of the last two decades that goes unmentioned by Vaheesan is the stagnation of load growth on the US grid. The legibility of this fact as a political achievement reveals an important aspect of our dilemma, especially in light of current utility projections for massive data center-driven load growth. In addition to exempting wholesale generators from federal rate regulation, the 1992 Energy Policy Act also targeted demand, creating efficiency standards for buildings, lights, and electrical appliances. During the second Bush administration, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 reinforced these efforts (while striking down what remained of the New Deal’s hallmark attack on concentration, the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935). As the energy efficiency of appliances improved, load growth stagnated.8

On the supply side, greenhouse gas emissions declined significantly. Despite the fact that many states adopted “renewable portfolio standards” in the 2000s, the largest reductions up to the 2020s have come from replacing coal with ever-cheaper natural gas. The 1992 Energy Policy Act launched the Department of Energy’s Advanced Turbine System program, a cost-sharing research initiative with turbine manufacturers. Gas combustion turbines—the majority of which are made by General Electric and Siemens, two well-established companies who took advantage of the DOE’s turbine program—became significantly more efficient than their steam turbine counterparts. Many have become used in an even more efficient “combined-cycle” setup that recaptures exhaust heat from the combustion turbine and recycles it through a steam turbine.9 Even more recently, the US has presided over the largest increase in gas production by any country in world history with the commercialization of horizontal drilling technology, or “fracking.” After 2008, gas prices were cut in half almost overnight. Along with certain clean air regulations that applied principally to coal power plants, these developments made gas a much more economical option for power generators than coal and nuclear.

Vaheesan definitively summarizes the geographic differences of restructuring under deregulation in a chapter with the suggestive title, “Institutions Serving Two Masters.” He does not, however, weigh the effects on decarbonization of these restorations of shareholder power. Alongside turbine innovation, fracking, and clean air regulations, electricity restructuring reinforced the dash for gas by power companies. Although the transition to gas ultimately became a national trend, it initially proceeded furthest in restructured areas. Investor-owned independent power producers entered these markets in droves, bought up former utility generating plants, retired or converted those that burned more coal, and built new gas-fired plants of their own.10

As coal use diminished, new emissions reductions have come more and more from resources like wind and solar. The majority of wind and solar farms are also financed and owned by independent power producers (including large companies like NextEra and Clearway). They exist mainly in areas with competitive wholesale markets, and especially in the “energy only” markets of California and Texas—markets that do not compensate generators for the reliable power capacity of fossil fuel plants. Renewable generator profits are both low and uncertain in most competitive power markets around the world, the US included, as prices are cheapest on sunny days and windy nights.11 Despite this, however, it is in these restructured markets that investors are financing renewables projects at an increased rate.

The Southeast, Midwest plains, and mountain states have in large part retained state commission rate-regulation of vertically-integrated, investor-owned monopoly utilities as their primary model of governance. They are more reliant on fossil fuels and, in some cases, nuclear power, as regulatory capture by investor-owned utilities is keeping renewables out of the protected market. (Some Plains states with low total power needs also have a high share of wind.) Although the geography of natural resources plays a role, these differences in the composition of generating capacity follow from legal and regulatory environments at the state and regional level. But the fact that it is Texas—the most ramshackle, neoliberal electricity market region with the most permissive permitting process in the country—that is now the overwhelming leader in the US renewables boom should at least give advocates of decarbonization through public power a lengthy pause. Although wholesale power markets are by no means a necessary condition for renewables growth, restructured states with more independent power producers are building the most solar and wind and doing it the fastest. This has helped to obscure the relation between democracy and decarbonization to the disadvantage of activists committed equally to both.

For advocates of a “just transition,” the other side of the equation is environmental, climate, or energy justice—concepts that often elude precise definition. To the extent that justice (or rather injustice) in the electricity sector can be identified by unequal burdens resulting from prices, pollution, and service reliability, the results of restructuring and the transition from coal to gas are extremely mixed. On one hand, advocates of deregulation and restructuring have promised rate reductions that have not consistently materialized, in part because electricity prices are more tightly coupled to deregulated gas prices, which are prone to volatile swings. Furthermore, electricity prices in deregulated markets spike during hot summer or cold winter days and fall heaviest on low-income households. On the other hand, the switch from coal to gas has reduced (but by no means eliminated) disparities in harmful air pollution exposure between income and racial groups. Meanwhile, the grid as a whole has become less reliable: the number of outages has ticked up in the last few decades. This development is driven primarily by the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events. But lackluster maintenance spending by both investor- and government-owned companies exacerbates the problem. Outages from storms tend to last longer in low-income areas.12

Existing public power organizations are no panacea to these problems, as Vaheesan acknowledges. In Senator Norris’s home state of Nebraska, where public power organizations cover the entire state, the Omaha Public Power District, citing grid reliability concerns, has continued to extend the life of the state’s most polluting (on a per-MWh basis) coal plant, located in a poor, majority black area in a highly segregated city with the highest asthma rates in the state.

Understanding the scale of the problem of governing electricity, and its role in the historical development of the US political system, allows us to appreciate more fully the challenge of Democracy in Power. Electricity demand growth today has come roaring back, largely driven by data centers performing energy-intensive computational procedures. With the partial exception of the switch from one fossil-fuel to another, there has moreover never been a true energy transition in the US electricity mix.13

At the same time, there is a dauntingly long list of political predicaments that bear on the problem of democracy in the US energy transition—among them, the vested interests of vertically-integrated fossil-fuel-dominated utilities and their gas suppliers, renewable gains made primarily by large shareholder-owned companies, courts that have placed partial limits on the authority of executive administrative agencies with decarbonization plans, escalating political and economic conflict with the world’s preeminent producer of solar panels, and an entrenched bipartisan political coalition that seems little committed to either democracy or decarbonization. Although Vaheesan’s policy proposals are compelling for the ideal of democratic accountability—which, in the power sector at least, has eroded markedly since the 1970s—the prevailing patterns of ownership in the transition to gas and the boom in renewables paint a more complex picture of the relationship between democracy and decarbonization. Will people interpret their role in a significantly hotter future as passive consumers? Will the political history of climate change in the US be remembered as a market-based fait accompli—the paternalism of government by business? It is on these higher terms that Democracy in Power’s full import comes to bear. For, as the most recent federal push for decarbonization demonstrates, the institutions of the market have obscured from Americans their own role in governing themselves and their society. Accelerating this trajectory while ensuring it proceeds in a more just manner remains, therefore, an incredibly arduous political challenge.

FootnotesFor an example of each, inter alia, see: David Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992); Andrew Needham, Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014); Julie Cohn, The Grid: Biography of an American Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017).

Pyramiding referred to the investment strategy of owning holding company common stock that, through multiple layers of ownership, translated minuscule overall ownership shares into effective control of income-producing properties.

There is a long-standing debate amongst historians, mostly economic historians, about the particular motivations for the establishment of state utility commissions, which include corporate capture, economies of scale, and Progressive anti-corruption advocacy, to name a few. For a succinct summary of the debate, see: John Neufeld, “Corruption, Quasi-Rents, and the Regulation of Electric Utilities,” Journal of Economic History 68, no. 4 (Dec. 2008): pp. 1059-1097, especially the section entitled, “Empirical Studies on the Origin of Electric Utility Regulation.”

Richard Hirsh, Technology and Transformation in the American Electric Utility Industry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Despite the fact that these “qualifying facilities” competed with utilities to generate power, utilities were also their primary customers, since utilities owned the transmission and distribution infrastructure to deliver power to customers. In the event they could not generate power sufficient to satisfy demand they would be required to purchase it. As PURPA suggested, rates for qualifying facility power were to be determined by the utility’s “avoided cost.” Much like “fair valuation” of property, determination of “avoided cost” was left subject to state commissions, and could therefore differ widely by state. At the turn of the early twentieth century, before central electric utility stations became widespread, industrial manufacturers often produced their own electricity, competing with utilities. To secure the business of manufacturers, utilities offered manufactures lower prices than they might pay to produce power themselves. For more on the political bargaining and interest group lobbying surrounding the creation and implementation of the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978, see: Richard Hirsh, Power Loss: The Origins of Deregulation and Restructuring in the American Electric Utility System (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), especially Chapters 3 through 7.

At the time, electricity, unlike a manufacturer’s inventory, was not easily stored. This made investment in new generating equipment a function of a utility’s maximum demand. This, in turn, made utilities by far the most capital-intensive sector of the economy in the early twentieth century. Investor-owned utilities, therefore, quite reasonably found it difficult to finance the expansion of residential service and lower their rates without also increasing what is known as the “load factor” (the ratio of the average to the maximum demand over a given time period; a measure of capacity utilization or efficiency). Typically, utilities raised their load factor by relying on price discrimination: they offered lower rates to industrial customers, who used power throughout the entire day and sometimes night, in order to incentivize them to either switch to or use more central station power rather than onsite power, raising utilities’ revenues relative to their large capital costs. This allowed them to also lower residential and commercial rates, but not to the same levels as industrial rates. See, inter alia, Thomas P. Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880-1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), and John Neufeld, Selling Power: Economics, Policy, and Electric Utilities Before 1940(Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2016). The early twentieth century municipal franchise “era” of utility regulation, as it is sometimes called, led to immense amounts of political corruption, as officials in numerous cities extorted their local utilities and accepted bribes from them in exchange for favorable treatment. See: Lincoln Steffens, The Shame of the Cities (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1904).

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Campaign Address in Portland, Oregon on Public Utilities and Development of Hydro-Electric Power,” The American Presidency Project, September 21, 1932. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/289311.

Richard F. Hirsh and Jonathan G. Koomey, “Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth: A New Relationship with Significant Consequences?” The Electricity Journal 28, iss. 9 (November 2015): pp. 72-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2015.10.002.

Kelly A. Stevens, “Analysis of the Advanced Turbine System Program on Innovation in Natural Gas Technology,” Energies 13, no. 19: 5057 (September 2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/en13195057.

Jean-Michel Glachant, “Generation technology mix in competitive electricity markets,” in Competitive Electricity Markets and Sustainability, ed. Francois Leveque (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2006), pp. 54-86; Alexander Hill, “Excessive entry and investment in deregulated markets: Evidence from the electricity sector,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 110: 102543 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102543.

See Brett Christophers, The Price is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet (New York: Verso, 2024). As Christophers points out, many energy commentators point to low prices for renewables as a reason for their recent growth. He argues that this assertion gets things backwards. In fact, low prices imply low and uncertain profits for renewable generators. Rather than a catalyst, this is an impediment. The fact that it is the “energy only” wholesale markets—where generator profits are not guaranteed by traditional cost-of-service rate regulation—that are seeing the most renewable growth within the US thus presents a paradox for Christophers’ book as applied to the case of the United States.

Vivian Do, et al., “Spatiotemporal distribution of power outages with climate events and social vulnerability in the USA,” Nature Communications 14: 2470 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38084-6.

Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy (London: Allen Lane, 2024).

Filed Under