This year, we once again shattered the record for atmospheric carbon concentration, and witnessed a series of devastating setbacks in US climate policy—from attempts to waive state protections against pipelines to wholesale attacks on climate science. Against this discouraging backdrop, one idea has inspired hope: the “Green New Deal,” a bold vision for addressing both the climate crisis and the crushing inequalities of our economy by transitioning onto renewable energy and generating up to 10 million well paid jobs in the process. It’s an exciting notion, and it’s gaining traction—top Democratic presidential candidates have all revealed plans for climate action that engage directly with the Green New Deal. According to the Yale Project on Climate Communications, as of May 2019, the Green New Deal had the support of 96% of liberal democrats, 88% of moderate democrats, 64% of moderate republicans, and 32% of conservative republicans. In order to succeed, however, a Green New Deal must prioritize projects that are owned and controlled by frontline communities.

Whose power lines? Our power lines!

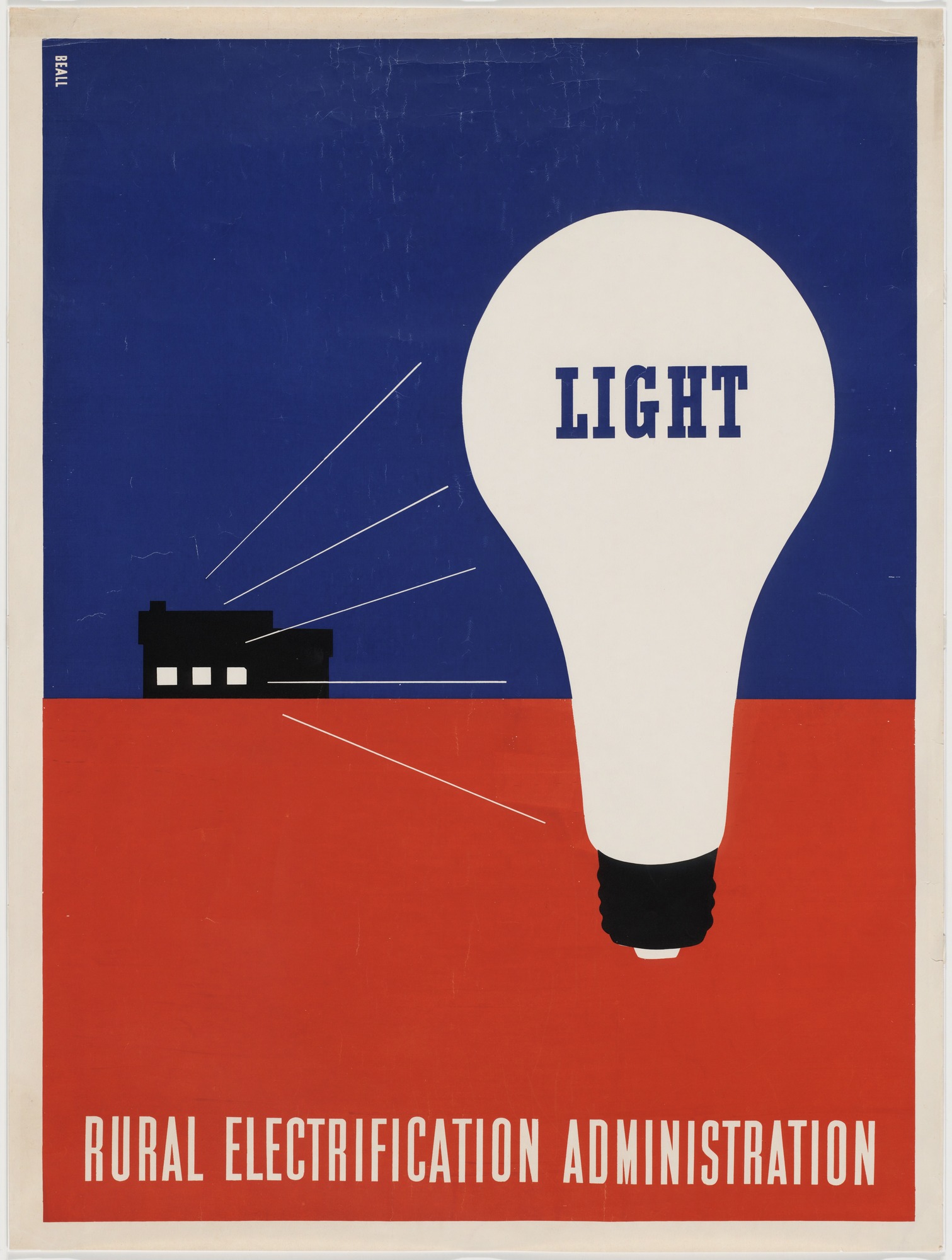

Efforts to electrify the rural South during the New Deal present a useful case study for understanding the impact of ownership models on policy success. Up until the mid-1930s, 9 out of 10 Southern households had no access to electricity, and local economies remained largely agricultural. Southern communities were characterized by low literacy rates and a weak relationship to the cash nexus, distancing them from the federal government both culturally and materially. They were also economically destitute—a series of droughts throughout the 20s led to the proliferation of foreclosures and tenant farming. With the initial purpose of promoting employment in the area, the Roosevelt administration launched the Rural Electrification Administration in 1935. The Rural Electrification Act of 1936 sought to extend electrical distribution, first by establishing low-interest loans to fund private utility companies. The utility companies turned them down: private shareholders had little reason to invest in sparsely populated and impoverished counties, whose residents could not be assured to pay for services; private investors lacked the incentive to fund electrification for the communities who needed it most.

In response, farmers, business owners, and housewives throughout the South formed cooperative distribution companies called Rural Electric Cooperatives (RECs), offering to own and run the distribution infrastructure using the loans that the federal government had originally allocated to corporations. By the end of 1936, nearly 100 cooperatives across 26 states signed loan agreements with the REA. 53,000 miles of power lines were constructed within the first two years of the agreement, cutting local electricity prices by more than 50 percent. The project was so successful that in 1937 the federal government passed the Electric Cooperative Corporation Act, which directed states to pass model legislation allowing new cooperatives to form. By 1939, 288,000 rural southern households were electrified for the first time in the history of the country.

Early electrification efforts differed from their more successful iterations in the sort of incentive structures that they promoted. The farmers who offered to own and run the distribution infrastructure were not merely motivated by return on investment—they occupied the dual position of both workers who needed jobs, and members of communities who relied on the electrical power those jobs would provide. As a result, the RECs were willing to accept a lower rate of profit from energy sales.

The Roosevelt Administration’s unique management of the natural monopoly of electrical utilities fostered the leadership of the communities who stood to benefit from the program. In a 2000 article, Brian Cannon describes the dynamic process of cooperative formation: local merchants or businesspeople learned about the availability of funds from radios and newspapers, and took the initiative to contact the Rural Electrification Administration. The administration would then group interested citizens in the same geographic region, encourage them to form an elected steering committee, and develop plans for a loan. Cannon writes:

Before applying for a loan, committee members identified the rates at which the nearest utilities would sell electricity to a consumers’ cooperative. They held mass meetings, spoke to civic organizations, and persuaded local newspaper editors to publish articles regarding rural electrification in order to arouse interest in the program. Then they canvassed the community, asking prospective customers to complete a form confirming their interest in securing electrical service and estimating the amount of power they would use. Finally, they outlined routes of proposed power lines and pinpointed each customer’s home on detailed maps. All of this work, performed by local residents without compensation, demonstrates how strongly rural electrification was a grass-roots initiative.

To bring the historical comparison to the present, we don’t need to look any further than the Rural Electric Cooperatives themselves—RECs still provide power to 42 million ratepayers in this country across 47 states. In a 2017 essay, Kate Aronoff outlines the political potential of these entities, describing how dedicated activism has ensured that the Roanoke Electric Cooperative (one of the few RECs in the country with a majority black board and staff) prioritizes local job creation and holistic community benefits in its programs. These benefits include “inclusive financing” for energy efficiency upgrades, allowing members to access energy efficiency benefits with no up-front cost, providing credits for any fees that aren’t invested into grid maintenance, and giving people the ability to collectively fund libraries, school trips and other programs that benefit the community. As Aronoff put it, “It’s a clear win-win: member-owners save money on their monthly bills, while the coop saves money on overheads and creates jobs for the people in their service area.”

In parts of the country where Americans are suffering from a lack of jobs, pollutants from fossil fuel generation, and a need for cheaper electricity, policies which build on the model of RECs are likely to see similar support and success.

The tightrope: race and power

As historians such as Ira Katznelson and Richard Rothstein have pointed out, the old New Deal both ossified and inaugurated new spheres of racial inequality. Through racist homeowner lending practices, and—in the South—through the exclusion of domestic and agricultural laborers from protections under the Wagner Act, at a time when 41% of Southern black workers were employed in agriculture and 63% of black women worked as domestic workers, the gains of New Deal programs were marked by the color line. There’s a clear difference between what the New Deal accomplished for white and black workers, and RECs demonstrate both the racial politics of the time, and the potential of worker ownership to serve as a stepping stone in overcoming them.

The very first rural electric cooperative formed under the auspices of the New Deal was the “Corinth Experiment,” a cooperative formed in Alcorn County, Mississippi in 1934. The first meeting of the Alcorn County cooperative was convened in a Mc Peters’ Furniture Store by Mississippi Congressman John Rankin, who was one of the leading advocates for the New Deal’s efforts to electrify the South. This same Congressman Rankin would fight for segregation throughout his political career, explicitly calling for legal segregation in the halls of Congress and in the media. As with the Wagner Act exclusions, the effort to electrify the South was defined by the white supremacist ideology of those who were implementing this effort, which has had lasting consequences for the RECs themselves: a study from 2016 found that among 3,000 board members of southern RECs, only 90 black people served in board positions.

There are many lessons here—not least of which is America’s tendency to gloss over the racism of its signature progressive policies. For policymakers and advocates of the Green New Deal, perhaps the most salient lesson is that sustainable and effective economic relief depends on restructuring political power. For white southern farmers who participated in RECs, the political power that was guaranteed by ownership ensured that they populations would benefit in perpetuity. For black farmers, domestics and workers, the preconditions for political power were never established. Any version of a Green New Deal must ensure that power accrues in the hands of the frontline communities who were historically excluded from the previous New Deal, and who currently suffer the greatest harms from the twin crises of climate change and our existing energy system.

As of 2018, there are more clean energy jobs in the U.S. labor force than there are fossil fuel jobs, despite renewable energy making up only about 11.38% of the energy we consumed that year. If the Green New Deal significantly augments the renewable share of our generation market, it would not only be possible to revitalize employment for millions1, but do so in a way that embeds the power of workers, and especially workers of color, into the economy. Many of the most important decisions over our electric system are made at the state level—each state’s department of public service controls the price and source of electricity for its residents. As local communities gain ownership over a larger share of generation resources, their political power grows, as does their ability to write policies that meet public ends. This symmetry between policymaking and local needs in turn increases the likelihood that legislation enacted to benefit these communities will last.

This dynamic is integral to the strategy of Cooperation Jackson, a Black-led self-determination organization based in Jackson, Mississippi. Mississippi is the poorest state in the nation, and Black workers in Jackson grapple with exploitation and oppression on multiple fronts. To that end, Cooperation Jackson has organized along an “inside-outside” strategy to wield direct power over resources and political decision-making. Their efforts resulted in the election of Chokwe Lumumba as mayor in 2017. Co-Director of Cooperation Jackson Kali Akuno explains why climate change is among the organization’s top priorities in his co-authored book, Jackson Rising: “The second critical contradiction we are trying to exploit involves the ecological limits of the capitalist system. We plan on exploiting this contradiction by turning the economic strategies proposed to address the climate crisis on their head.” (Read Akuno’s full analysis here.) In Mississippi, it is illegal to sell community generated electricity back to the grid, limiting the ability of communities to develop cooperative renewable energy projects. Cooperation Jackson is therefore considering how to organize coop beneficiaries in order to change these laws. Organizations that prioritize community ownership enable a positive feedback loop between projects and policy.

We can see it from here

Specific features of the Green New Deal have yet to be determined. Progressive think tank New Consensus has been working closely with Ocasio-Cortez’s office, soliciting feedback from environmental justice organizations across the country in order to develop policy details. Whether the final policy will integrate this feedback remains to be seen. To clarify their position, the members of the Climate Justice Alliance (CJA) published a statement in December 2018. They argue that, having organized their communities to support a regenerative economy for many years, they have an unparalleled claim on the expertise necessary to develop a new energy system.

This is the good news—in the CJA and its member organizations, we have a blueprint for what a frontline ownership model in the Green New Deal could look like. The question is whether or not those in the driver’s seat will support these models. Over the next few months, Green New Deal proposals will likely emerge in statehouses across the country. We will see, based on this process, how well policy makers have learned the lessons of the past, and how willing they are to fight for our future.

To get all future Phenomenal World posts directly in your inbox, sign up here.

- The precise number of jobs that would be created is difficult to ascertain without more implementation specifics, but it’s worth noting that a 2009 study from the Union of Concerned Scientists found that a plan to increase renewable energy’s share of our generation to 25% would create roughly 297,000 new jobs – the Green New Deal, operating under a similar timeline, is proposing a 100% share of generation. ↩

Filed Under