Since 1999, the European Union (EU) and Mercosur have been negotiating a bi-regional partnership agreement comprising three pillars: trade, cooperation, and political dialogue. A quarter century later, in December 2024, the parties announced the conclusion of negotiations during the Mercosur Summit in Montevideo, attended by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Before implementation, the agreement will undergo legal scrubbing for national ratification processes. The European Union has opted for a split approval: the trade dimension of the agreement requires only European Parliament approval, while political and cooperation aspects must be submitted to national parliaments. Within Mercosur, though each country’s parliament must ratify the text, the agreement can take effect bilaterally between the EU and individually approving Mercosur nations.

A previous version of the deal was announced in 2019, under the Mercosur leadership of Jair Bolsonaro. Latin America abandoned those negotiations after the EU introduced new environmental regulations. While Bolsonaro opposed these measures, they were also widely viewed throughout Mercosur, including by progressive factions, as protectionist on the part of the Europeans. Negotiations resumed in 2023 with Lula’s new term. Although more moderate, the new text still faces criticism from organizations and governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the European Union, resistance comes primarily from agricultural sectors in France, the Netherlands, and Poland, which fear competition with Mercosur’s producers. In South America, concerns arise mainly from civil society and academia, centered on the agreement’s potential to undermine current reindustrialization efforts within Mercosur countries, reinforcing their export profiles focused on primary goods. Compared to 2019, the current version maintains greater freedom for the national implementation of public policies and public procurement requirements, enhanced environmental commitments, new review and “rebalancing mechanisms” in the case of disputes, and extended deadlines for trade liberalization or tariff removal in certain sectors.

Phenomenal World’s senior editor Maria Fernanda Sikorski spoke with Marta Castilho, professor of economics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and coordinator of the Research Group on Industry and Competitiveness (GIC-UFRJ), about the agreement’s perspectives for Mercosur—and Brazil, in particular—and the risks of trade liberalization for South America’s national and regional development. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

An interview with Marta Castilho

Maria Sikorski: Could you describe how the political and economic environment evolved during the partnership’s negotiation period, from 1999 until its conclusion in 2024? Why did the agreement remain relevant, and how did EU-Mercosur trade relationships change during this time?

Marta Castilho: When negotiations began, the European Union was a bloc of fifteen member states. Mercosur had aimed to gain preferential access to the European Union over Eastern Europe, which then had industrial structures relatively similar to ours. Eastern Europe, however, eventually became closely integrated with Western European industry. This might have been the most significant change since negotiations began, at which time the horizon was a little more encouraging to our industry.

Since the beginning, Mercosur saw an opportunity to increase exports of agricultural products. Domestically, the agreement was supported by interests linked to agribusiness, while industrial sectors took a more cautious approach, advocating for a gradual trade opening as they feared increased competition from European manufacturing.

Additionally, it was important to consider that European companies maintained a strong presence in the region through multinational subsidiaries, and their positions had, let’s say, “mood swings” throughout negotiations. For example, one of the world’s largest poultry producers, a French company with operations here in Brazil, initially supported trade liberalization because their aim was to raise chickens in Mercosur and export the meat to Europe. This is in contrast with current objections coming from France. Similar shifts occurred across various sectors. The automotive sector is another significant example, as is the chemical sector and its various subsectors, due to the strong presence of European companies in our region. In general, Europe showed great interest in opening Mercosur’s industrial products market and facilitating service flows. In contrast, there was stronger resistance to agricultural product imports.

MS: An earlier version of the agreement announced in 2019 never received European Parliament ratification. What are the main changes in the current text?

MC: One relevant factor is that in the five years between 2019 and 2024 the Covid-19 pandemic happened. By 2019, European countries were already signaling a return to industrial policies, with new strategies focused on “Industry 4.0,” digitalization, and related areas. The pandemic exposed some of these countries’ vulnerabilities, leading them to explicitly adopt policies targeting localized production and reducing foreign dependency in specific sectors and segments. This shifted the EU’s trade interests in the agreement and the overall negotiating conditions between the blocs.

The shift particularly affected the interest in minerals, especially critical minerals. Mercosur is extremely rich in mineral sources—in this regard it is a paradise. One of the most recent shifts is Europe’s increasing attraction to the region’s minerals. The EU has taken a dim view of any initiative inside Mercosur countries to protect or tax these mineral exports, but Mercosur has been strategic about the critical minerals sector, ensuring the possibility of imposing conditionalities.

In Brazil, there is an ongoing debate about this matter. The discussion is not closed, and perspectives vary, for example, between the government of the State of Minas Gerais and parts of the Federal government. The discussion centers on developing a strategy for critical minerals beyond its exploitation and export as raw material, to focus on increasing processing capacity and, ultimately, manufacturing batteries and other goods domestically.

Another change between the 2019 and 2024 texts concerns public procurement. Mercosur secured the right to use this mechanism as a productive development policy. While Europe has long employed public procurement, the 2019 agreement eliminated the possibility of Mercosur using certain mechanisms. Mercosur managed to renegotiate this, bringing the agreement’s terms much closer to the bloc’s existing rules. This was one of the most positive aspects of the renegotiation.

MS: What are the implications of separating the agreement’s trade, political, and cooperation pillars, given that trade provisions take effect after the approval of European Parliament and Mercosur national parliaments, while political and cooperation clauses require approval from each EU national parliament?

MC: The partnership agreement follows a European tradition of handling non-trade aspects in negotiations of this nature, unlike the Anglo-Saxon tradition, for example. This is the reason why the EU-Mercosur agreement has a trade component, a cooperation component, and one for political dialogue. This is a positive aspect of the agreement because, for example, cooperation provisions could compensate for certain trade-related losses. Trade opening can be compensated by prospects for cooperation in technical development in areas in which Europeans are more advanced, such as technology, and in fields where we can exchange, like bioeconomy and tropical medicine.

Now, for pragmatic and strategic reasons, the agreement has been split up. This is because a trade agreement is easier to negotiate and approve. The procedure, even within the EU, is faster: if it’s just the trade portion, it doesn’t require approval from all member-state parliaments but only the European Parliament. A comprehensive partnership agreement would need to go through all national bodies—a process that could be delayed by the disagreements we’ve seen in France, Poland, and the Netherlands, for example. For the Europeans, it’s a pragmatic matter. But for Mercosur, in my view, it’s short-sighted, as the bloc misses the opportunity to benefit from potential gains that would be made possible by other aspects of the agreement, especially cooperation.

MS: Because it is possible that only the trade agreement obtains approval while other pillars remain indefinitely postponed.

MC: Precisely, because there is no incentive to approve. You won’t put to a vote something you know won’t be approved. European interests are already covered by the trade agreement. For example, some environmental rules added to the current text—such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for disputes and the reforestation mechanism—do not affect the main European legislation: they are exempt from the trade agreement.

MS: Let’s discuss the trade agreement’s key aspects and their impact on different Mercosur sectors. Can we start with the part about tariffs and tariff rate quotas?

MC: The trade agreement covers various regulatory domains. One of them is tariffs and tariff-rate quotas—quotas are technically non-tariff barriers, but they are typically addressed together. The quotas are largely used for agricultural products: a lower tariff is applied for a certain amount of exports within the agreement, and anything exceeding this quota is charged with standard partner-country rates. Mercosur countries adopt a common tariff for agricultural products. The current agreement maintains an array of tariff-rate quotas from the 2019 text. Certain products see increased quotas and reduced in-quota tariffs. In other situations, the in-quota tariffs were reduced, but the established quota is lower than the amount we were already exporting in 2019 and 2020. Moreover, there are mechanisms which allow Europeans to review these quantities—another preserved aspect of the 2019 text. While Mercosur may gain improved access to the EU agricultural market, trade liberalization is not as impactful as some sectors hope or proclaim.

MS: Considering the volume of our current exports?

MC: Exactly. But some segments will benefit. Take beef producers, for example—it’s no surprise that French farmers are highly reluctant, as beef is one of the products receiving expanded quotas and reduced tariffs. Rice was one of the products for which both quotas and tariffs on imports into Europe were reduced. There are various situations among agricultural products.

MS: What about Mercosur’s industrial goods?

MC: That’s our biggest problem, for several reasons. European tariffs on industrial goods are already quite low: in general, they average around 5 percent, while ours will settle near 13 percent. Potential tariff reductions by the Europeans on our exports there are modest and Europe’s existing trade agreements with other countries further limit our preferential margin. On top of that, there’s a significant asymmetry, both in terms of competitiveness and scale of our industrial sectors. While we lack the competitive advantage to significantly penetrate European markets, their potential gains from trade liberalization are much greater.

MS: The general perception in critical assessments of the agreement suggests that Mercosur’s agribusiness would benefit significantly while industry would struggle. But from what you are saying, the agricultural sector doesn’t necessarily gain that much, except in specific products.

Given this scenario, what implementation conditions would help South American industry benefit, or at least mitigate negative impacts of competition with European industry?

MC: The trade and tariff liberalization is already set and will likely be implemented. What this means is that, in trade terms, there’s little to be done. On the one hand, we need to enhance domestic industry productivity and competitiveness—and that’s our own responsibility, which involves conceiving industrial and productive development policies, making strategic use of public procurement, and implementing technological policies. On the other hand, we can also make use of certain adjustment mechanisms within the agreement, such as the rebalancing mechanism. The revised text added certain safeguard mechanisms against occasional surges of products and abrupt inflows in specific sectors. While specific instruments await definition, at least the deal preserves adaptation possibilities.

Nevertheless, competition between our industrial production and Europe’s remains inevitable. What we can do is leverage available domestic tools to enhance our industrial competitiveness, while utilizing both national and agreement-based trade mechanisms.

MS: Tariffs represent a crucial tool for protecting and strengthening domestic industry in order to become competitive, especially for countries like those in South America. Doesn’t an EU trade agreement of this nature undermine efforts toward reindustrialization in the region?

European companies enjoy technological and productive superiority, better credit access, and stronger state support. Brazilian companies, conversely, face extremely high interest rates, scarce credit, currency instability, and logistical and infrastructure challenges. Aren’t we giving up a crucial industrial policy tool? Could this agreement reinforce Brazil’s trend of returning to a primary-export-based economy as has taken shape in recent decades?

MC: Absolutely. The agreement impacts it in both short and long-term. Short-term effects stem from tariff reductions. Even though the timeline for vehicle tariff reductions was extended, particularly for those with new technologies— the tariff reduction schedule for electric vehicles, for example, could extend up to 30 years—the current version doesn’t seek to revise the tariff reduction promised in 2019. We gave up on an instrument that could strengthen domestic industry in relation to a stronger trade partner, further complicating reindustrialization efforts.

Beyond tariffs, other crucial domains include public procurement, questions related to intellectual property, and so on. Securing public procurement mechanisms represents a significant achievement for Mercosur, and it’s worth noting that this is a hallmark of the current Brazilian government in the text. They insisted on this point, and now we will explicitly use it—just as developed countries do. This mechanism is particularly interesting, because it not only enables state support for specific sectors through preference margins and conditionalities but also helps to prompt certain practices—for example, requiring public procurement to be sustainable encourages suppliers to adopt sustainable practices. This applies both to domestic and foreign companies: if an international company wants to become a government supplier, it could, for example, face technology-transfer requirements.1

As for the intellectual property section, I get the impression that there haven’t been significant progress or reversals compared to 2019, which established slightly stronger commitments than those already made by WTO countries, but not much more than that.

Compared to previous versions, it seems that until around 2013 or 2014, the Brazilian government approached negotiations with a clear strategic vision centered on productive development and autonomy. That continuously shifted until 2019. While we might see some improvements now, the text retains several elements negotiated under a strongly liberal framework. The trade chapter, for example, has remained largely untouched.

MS: How might the agreement impact Brazil’s reindustrialization efforts?

MC: The trade part of the agreement undermines reindustrialization efforts targeting a more technologically dynamic and autonomous productive development. While some domains—such as public procurement and certain safeguards and rebalancing mechanisms—represent progress compared to 2019, they are insufficient.

Brazil’s large consumer market and position as South America’s export platform demand special consideration. So, it’s the Brazilian government’s role to try to impose conditionalities to compensate agreement-related losses. The mining sector offers a prime example. The government can potentially intervene in the conditions of mineral exploitation within national territory. There’s some room for negotiation with investors—for instance, by stipulating that certain advantages can only be accessed if more production stages occur domestically. However, this will depend on the domestic management of industrial, technological, fiscal, and tax policy instruments. It will also hinge on macroeconomic conditions, including growth potential and interest rate dynamics.

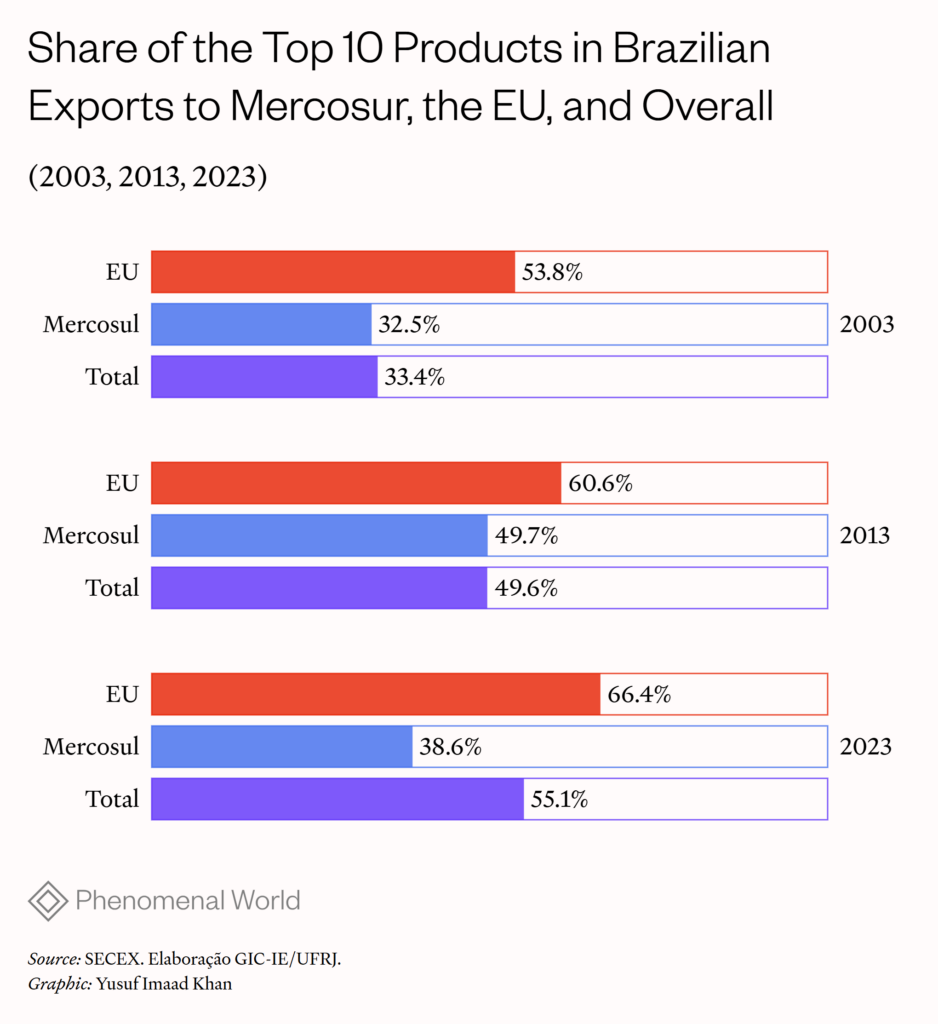

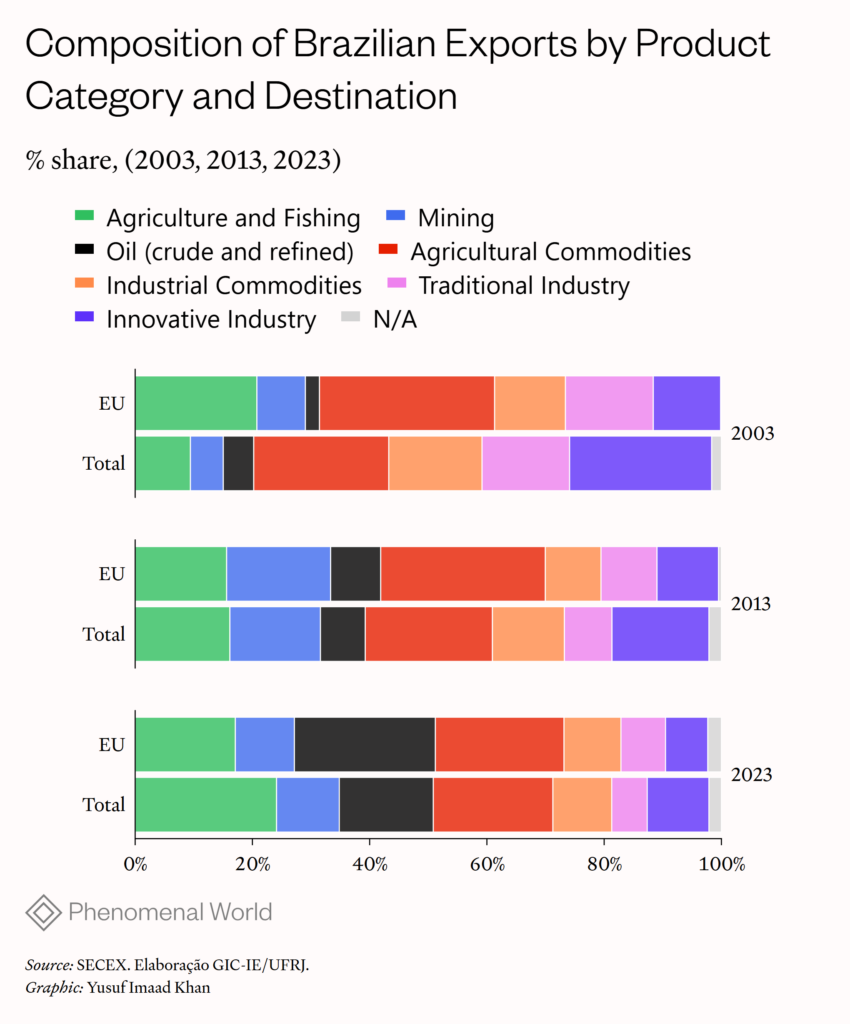

Moreover, it is important that the Brazilian government shares its advantages with other Mercosur countries. The problem with this agreement is that it tends to reinforce a pattern of growing regressive specialization, which has intensified since the 2000s across Brazil and the region. Comparing Brazilian exports to the EU in 2003, 2013, and 2023 reveals the increasingly primary nature of our exports profile. And the agreement tends to reinforce our specialization in agricultural and mineral products.

| Order | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Soybeans, whether or not ground | Iron ores and concentrates, including roasted iron pyrites | Petroleum oils and oils obtained from bituminous minerals, crude |

| 2 | Soybean oilcake and other solid residues from soybean oil extraction | Soybean oilcake and other solid residues from soybean oil extraction | Soybean oilcake and other solid residues from soybean oil extraction |

| 3 | Iron ores and concentrates, including roasted iron pyrites | Soybeans, whether or not ground | Coffee, whether or not roasted or decaffeinated; coffee husks and skins; coffee substitutes containing coffee in any proportion |

| 4 | Fruit juices (including grape must) and vegetable juices, unfermented, not containing added spirit, whether or not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter | Coffee, whether or not roasted or decaffeinated; coffee husks and skins; coffee substitutes containing coffee in any proportion | Soybeans, whether or not ground |

| 5 | Coffee, whether or not roasted or decaffeinated; coffee husks and skins; coffee substitutes containing coffee in any proportion | Chemical wood pulp, soda or sulfate, other than dissolving grades | Copper ores and concentrates |

| 6 | Chemical wood pulp, soda or sulfate, other than dissolving grades | Petroleum oils and oils obtained from bituminous minerals, other than crude; preparations not elsewhere specified or included, containing by weight 70 percent or more of petroleum oils or of oils obtained from bituminous minerals, these oils being the basic constituents of the preparations; waste oils | Iron ores and concentrates, including roasted iron pyrites |

| 7 | Meat and edible offal, of the poultry of heading 0105, fresh, chilled or frozen | Petroleum oils and oils obtained from bituminous minerals, crude | Chemical wood pulp, soda or sulfate, other than dissolving grades |

| 8 | Unwrought aluminum | Fruit juices (including grape must) and vegetable juices, unfermented, not containing added spirit, whether or not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter | Fruit juices (including grape must) and vegetable juices, unfermented, not containing added spirit, whether or not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter |

| 9 | Petroleum oils and oils obtained from bituminous minerals, crude | Unmanufactured tobacco; tobacco refuse | Petroleum oils and oils obtained from bituminous minerals, other than crude; preparations not elsewhere specified or included, containing by weight 70 percent or more of petroleum oils or of oils obtained from bituminous minerals, these oils being the basic constituents of the preparations; waste oils |

| 10 | Unmanufactured tobacco; tobacco refuse | Copper ores and concentrates | Ferro-alloys |

Thus, strengthening regional industrial coordination within Mercosur becomes crucial. Despite obvious political challenges, the existing coordination in certain sectors should not only be preserved but further reinforced—including through public procurement mechanisms or regional funds, enabling the bloc to enter more cohesively in this EU “partnership.” The Uruguayan government, for example, is delighted with the agreement—particularly because the liberal government that took part in the negotiations was fond of the specialization.2 Their beef exports do not face the same environmental problems as Brazilian production in the Amazon and Cerrado regions. For Brazil to maximize agreement benefits, coordinating with its neighbors and creating strategies to transfer part of the gains is desirable, as it could facilitate alliances with these countries and boost bloc-wide industrial production.

MS: The Brazilian government’s official position claims the agreement offers several advantages to Mercosur. The Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services, for example, highlights greater access to the European market—which could attract additional foreign direct investment—and reduced domestic costs for industrial inputs and capital goods—since we could import them duty-free. Improved international competitiveness of our products is the ostensible result. They argue this would strengthen trade partnership diversification, industrial modernization, integration with EU production chains, and spark interest from other actors in negotiating new agreements with Mercosur to access this market. How do you view this argument?

MC: This is a very old argument on trade liberalization. It is the same one used in the 1990s, claiming that we can import to export, that liberalizing imports might provide productivity gains through the import of cheaper inputs and capital goods. This would allegedly lead to competitiveness gains for the domestic industry, turning the country into an exporter of manufactured goods. However, since then, Brazil and the region have increasingly exported less sophisticated goods. In short, our major liberalization attempt implemented in the 1990s provided no evidence of the positive effects of trade opening on exports.

I doubt that this time the Brazilian economy will achieve a great virtuous cycle of economic growth driven by direct investment or increased export competitiveness through greater access to European inputs, particularly in the current context. Will we integrate into European value chains? No, we won’t. Europe has already established its chains and is attempting to shield itself from Chinese and other Asian countries’ entry, trying to consolidate these chains as much as possible within European borders. Our role will likely be further specializing in raw materials supply for these chains. The foreign investment we might attract relates to companies looking to take advantage of specific domestic factors, such as natural resources and a broad regional consumer market. But this does not necessarily translate to industrial modernization.

This article was translated from Portuguese to English by Glenda Vicenzi.

FootnotesN.E: Public procurement compensation mechanisms from foreign companies are called offsets.

N.E: Uruguayan President Lacalle Pou’s neoliberal-oriented term ends in March, when progressive candidate Yamandú Orsi, allied with former president Pepe Mujica, takes office.

Filed Under