One of the questions at the heart of contemporary debates over the merits of UBI is ‘what would it fund?’ In other words, what type of activities would it encourage? There are of course the widely debunked quibbles about guaranteed income encouraging anti-social behaviors, but there’s also a feminist critique of basic income proposals.

The feminist case against a UBI centers around the fear that, in contrast to more robust funding for social programs such as subsidized child care or parental leave, UBI would disproportionately encourage women to leave the labor force to provide care work in the home—reinscribing the gendered division of labor against which women have long struggled. In this view, UBI is undesirable—expected to fund the isolation of women in the domestic sphere, and preventing them from wielding influence over the real machinations of society.

This concern has had remarkable staying power, perhaps in part because discussions on the topic have often been relegated to theory and fail to engage with existing empirical data. Indeed, voices of people who have provided trenchant and insightful arguments regarding their preference for income decoupled from work have been almost completely silenced in today’s debates around UBI—whether popular or scholarly. Two recently published articles attempt to remedy this lacuna and return to concrete evidence to unpack the persistent question: which activities might a UBI fund?

In a particularly important contribution, David Calnitsky, Jonathan Latner and Evelyn Forget (2019) examine survey data conducted during the 1970s Manitoba Income experiments. Over the course of several years, people who had received the “Mincome” responded to questions about their participation in the labor force, and their reasons for leaving if they had.

Although the survey’s design limits the information available—it did not give respondents the option of recording that they had left waged work to pursue, for example, community involvement or artistic practices—it still provides invaluable insights into, in the author’s words, “the ways this oft-debated antipoverty policy might operate once it makes contact with the real world. Analyzing the impact of Mincome on participants’ non-labor market activities infuses empirical insight into the mechanics of a controversial policy proposal that continues to be marked by a dearth of solid evidence.”

Calnitsky, Latner and Forget find, as some feminists fear, that women did depart the workforce due to family obligations at a higher rate than men. But departures from the workplace for reasons related to “family” account for a smaller proportion of exits than do “job/work conditions” or “education.” In other words, even at a time when there was a substantially higher expectation that women prioritize care work over other interests and obligations, the primary factor encouraging women to leave the labor force wasn’t the “pull” of caring, but rather the “push” of undesirable jobs.

While extremely valuable to researchers, survey data are not the only empirical sources we have to deepen our understanding of people’s activities when they’re no longer beholden to labor market participation for their survival. In a recent article, Frances Fox Piven and I returned to the welfare rights movement as an historical example that provides insights into how guaranteed income might impact the way people, and in particular women, choose to spend their days.

In the mid-1960s, grassroots welfare collectives began forming across the nation and by 1966 many of these had amalgamated into the National Welfare Rights Organization. Comprised primarily of poor women of color, and influenced in part by the successes of the civil rights movement, the group organized thousands of welfare recipients all across the country to expand benefits and challenge intrusive, arbitrary eligibility policies. As the movement progressed, and in response to increasing successes which emboldened their demands, the NWRO shifted their focus to the establishment of a guaranteed income for all.1 Feminists then, as well as today, have interpreted this goal as signaling a desire to return to a gendered family wage.2 Emblematic of this approach is historian Georgina Denton’s analysis, which argues that “welfare recipients focused on mothers’ roles as nurturers and providers… Even though many of these women also worked outside the home in low-income jobs, their lives tended to center on home and children.”

In our paper, Piven and I challenge this interpretation, arguing that many participants in the movement insisted on a different priority entirely: civic engagement and political activism. This insight comes into sharp relief during a 1968 congressional hearing on income maintenance programs, when welfare activist Beulah Sanders clashed with Representative Griffiths, the self-anointed “most dedicated feminist we have in Congress,” over the activities women would likely pursue with state provided incomes.

Representative Griffiths argued for the importance of adding work requirements to welfare benefits, claiming that they would help ensure “[welfare recipients] have a right to participate in the economy of this country.”

Sanders criticized this logic:

“I am not going to do that because I feel I am more valuable and I can do something else. This is one of those things these people are worrying about, that they are going to be pushed into doing [undesirable jobs] when they can be much more valuable doing something else… What they have that is going for them is the nitty-gritty stuff and that is out into the community, mixing with the people, finding out what their problems are, and trying to help solve those problems.”

Sanders challenged the pervasive fear that by rebuffing waged work, women would be cloistered in their homes, relegated to domestic activities. Instead, she asserts that they had more “valuable”—namely, political—tasks to attend to: going “out into the community, mixing with the people, finding out what their problems are, and trying to help solve those problems.” Sanders was far from the only recipient activist who emphasized the relevance of community engagement to the lives of these women.

Jackie Pope, a former NWRO participant and scholar argues, in just one of many examples of this in the movement’s records, that recipients’ “self confidence increased as they became astute political activists.” One recipient noted “we were used to begging; we never demanded anything—welfare rights enabled us to walk into a welfare center unafraid, dignified and secure in the knowledge that our needs would be met.”3

Ms. Wise, a former activist in a Brooklyn chapter of the National Welfare Rights Organization, reflected on her experience in the movement and the reverberations it had through other civic organizations even after its decline, saying, “I learned I am somebody. Welfare Rights meant a right to life—it freed me from emotional slavery. I am a person you can’t push aside, I have the right to be. Welfare Rights showed me that my counterparts are all around; knowing this, I no longer felt alone. Welfare Rights lives, I and other people are still active, struggling for a better life. PTAs, school boards, even political clubs have former welfare rights members and we continue pushing the welfare rights agenda.”3

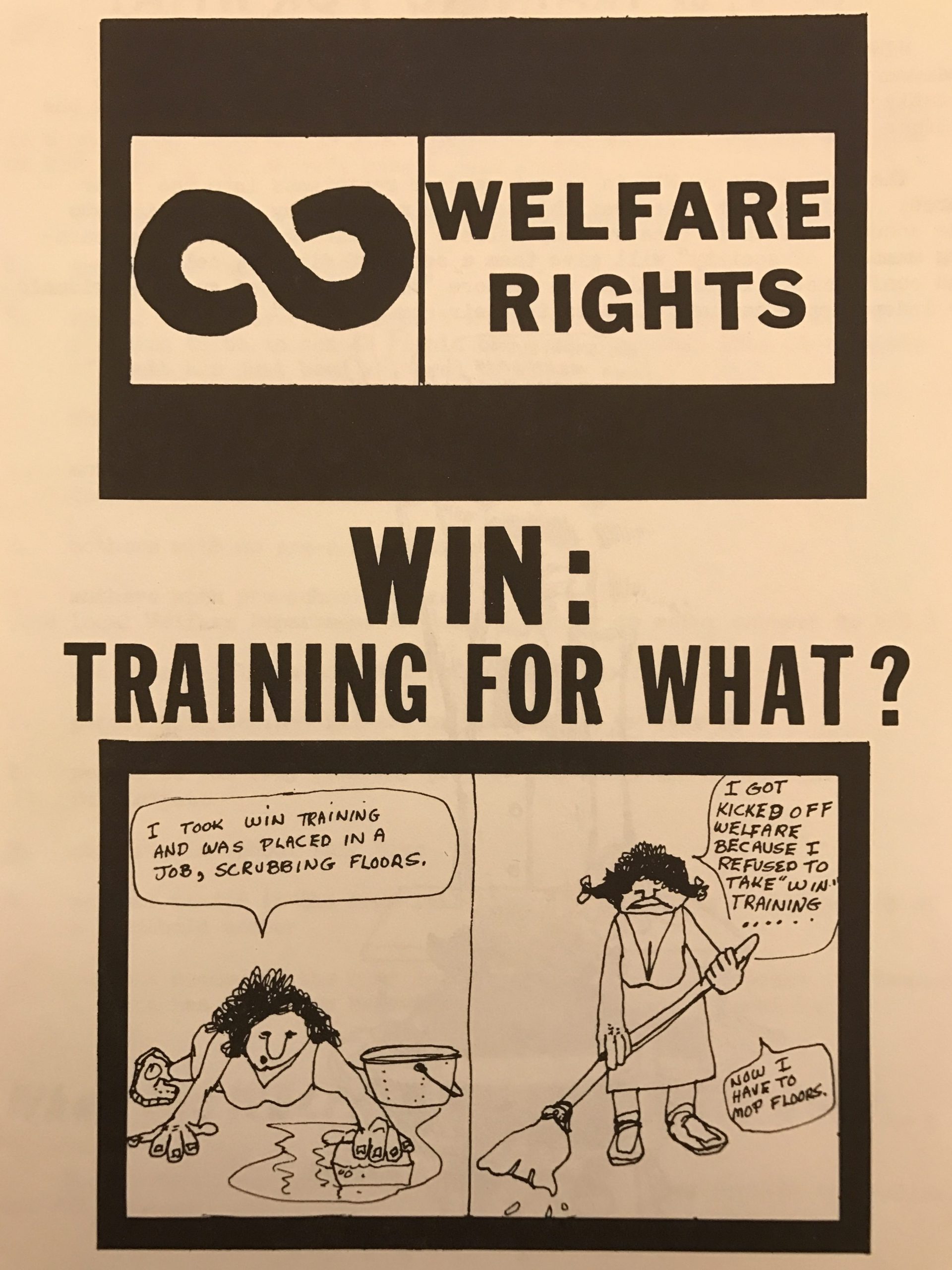

Again and again welfare recipients insist that in seeking a guaranteed income, they were not interested in simply retreating to domestic lives, but rather sought intense public engagement with issues of importance to their communities. This is underscored by their insistence on access to childcare whether they were working or not: “Mothers,” they noted, in a pamphlet critiquing a proposed welfare reform that would only provide childcare to women in the workforce, “especially need childcare that will free them for community involvement.”4

When we return to the archives of the welfare rights movement, what is glaringly apparent is not the domestic retreat many feminists fear a guaranteed income would encourage—and that some scholars insist they were seeking—but rather a remarkable level of civic engagement. Similarly, the evidence from the Mincome experiment encourages us to rethink the fear that UBI might cause women to run back to their homes. The evidence rather shows that the income provided them the means to leave bad jobs, and engage in more education. It would be difficult for any feminist to deny the individual and social benefits of these activities.

Without a doubt the social, political, and ecological crises we currently face require enormously creative, dedicated efforts to even begin to resolve. If, as the historical record suggests, there is the possibility that UBI might allow people to leave bad jobs, and free up time for some people to storm the offices of intransient fossil fuel beholden politicians, it is worth taking seriously.

- Sparer, Edward V. 1971. “The Right to Welfare.” The Rights of Americans: What They Are – What They Should Be 65: 1960–73.

- Several notable accounts: Ellen Reese. 2005. Backlash Against Welfare Mothers: Past and Present. University of California Press; Premilla Nadasen 2005. Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States. New York: Routledge. Marisa Chappell. 2011. The War on Welfare: Family, Poverty, and Politics in Modern America Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; Melinda Cooper. 2017. Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism. Near Futures. New York: Zone Books.

- Jacqueline Pope. 1990. “Women in the Welfare Rights Struggle: The Brooklyn Welfare Action Council.” In Women and Social Protest, edited by Guida West and Rhoda Lois Blumberg, 57–74. New York: Oxford University Press.

- NWRO Papers, Box 2179.

Filed Under