We often hear that the new Trump administration inaugurates the age of technofeudalism. Just look at Elon Musk, pontificating about so-called “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) democracy from the Oval Office while undemocratically occupying the US Treasury payment system. But is the administration simply using bullying as a mode of power, as Adam Tooze recently diagnosed it, destroying institutions without measure or plan?

The smashing of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) makes a good case for both. For American liberals, USAID stands as a beacon of progressive values—a vehicle for delivering essential public investments in sexual and reproductive rights, climate resilience, or the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in the global South. The many voices defending it from the DOGE onslaught have described it as a force for good, even as, or precisely because, it quietly advances US soft power objectives. This view is widely shared. As Bernie Sanders put it, “Elon Musk, the richest guy in the world, is going after USAID, which feeds the poorest people in the world.”

But this was not smashing without a plan. We learned in early February from Bloomberg that the Trump Administration planned to shift some USAID funding to the US International Development Finance Corp (DFC). Created during the first Trump administration, the DFC deploys public money to leverage or mobilize private investment overseas, in partnerships with institutional investors. As Bloomberg summarizes it: “The new approach would see reduced humanitarian assistance and a greater role for private equity groups, hedge funds, and other investors in projecting economic might as the US competes for influence and strategic projects overseas with China.”

At first glance, this looks like the privatization of foreign aid: a shift from public provision to market solutions. But there’s a larger story at play. The new Trump Administration is turbo-charging the lesser known but increasingly dominant agenda within USAID: “mobilizing private capital.” This approach, which I have termed the Wall Street Consensus, is a decade-old international development paradigm that has been promoted by the World Bank, the United Nations, and rich countries’ development agencies, including the USAID under the Biden Administration.

The Consensus reimagines the role of the state as a facilitator of private investment through various subsidies to investors that are often described as “derisking.” Development is no longer a public good to be directly financed by states, but a market opportunity to be unlocked through the alchemy of public-private partnerships (PPP) into “investible,” privately-owned projects.

USAID and the Wall Street Consensus

In its pre-Trumpian formulation, adherents of the Wall Street Consensus championed a vision of what it termed “investible development.” State and development aid organizations, including multilateral development banks, would escort the trillions managed by private finance into SDG asset classes, be those education, energy, health, or other infrastructure. The state derisks by using public resources—official aid or local fiscal revenues—to improve the risk-return profile of those assets, often described as bankable projects. In the energy sector, it commits to purchase private power at predetermined prices and/or predetermined quantities that guarantee a reliable cash flow for investors. A similar process takes place in investible health. In Turkey, for example, the Ministry of Health ended up spending around 20 percent of its budget on guaranteed payments for PPP hospitals co-owned by the French asset manager Meridiam, with an average cost per bed twice that of a public hospital. In water, public money for private water typically reduces universal access by imposing user fees on poor populations.

“Leveraging” or “mobilizing” private investment is code for granting public subsidies to privately owned social infrastructure. This involves a new distributional politics that shifts public resources to private investors. The for-profit logic at the core of this development paradigm curtails universal access to social infrastructure and is fertile ground for human rights violations. For example, Bloomberg reports that development aid-funded private hospitals in Africa and Asia have detained patients and denied care on a systematic basis.

USAID has also promoted “derisking private investment,” a fact celebrated by its former leader Samantha Power when she said late last year that: “USAID over the last four years has increased private sector contributions to our development work by 40 percent. For every dollar of taxpayer resources that we have spent, we have brought in $6 in private sector investment.”

When the Obama Administration made national security a primary focus for USAID programs, it launched Power Africa, a USAID energy initiative ostensibly aimed at improving energy access across the continent. On the now defunct USAID website, Power Africa presented several of its success stories, including the 450 MW Azura-Edo power plant in Nigeria and the Lake Turkana Wind Project and Kipeto Wind Project in Kenya, two of the largest renewable projects on the continent. If these projects, to some extent, represent important steps in closing the critical energy gaps blighting the continent, they nonetheless illustrate a familiar Wall Street agenda: USAID created opportunities for private financiers while imposing significant fiscal burdens on African governments and stunting opportunities for autonomous industrial upgrading. They have effectively worked as an “extractive belt,” channeling scarce fiscal resources of global South countries to global North investors.

Nigeria’s Azura-Edo natural gas powerplant is perhaps the most striking example of USAID-supported extractivism through derisking. The first privately-financed power project in Nigeria, the World Bank described it “as an example of how we have attracted private sector investment in the power sector.” To do so, the Bank, alongside official development institutions from the US (DFC), Germany, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands, organized and financially derisked bank lending to the project. But the fiscal derisking terms that Azura—now majority owned by the US private equity fund General Atlantic—extracted from Nigeria have been the subject of ongoing controversy.

The Nigerian state, via its state-owned Nigeria Bulk Electricity Trading, signed a $30 million-a-month take-or-pay agreement. Since Azura’s installed capacity could not be easily absorbed by the dilapidated Nigerian energy grid infrastructure, the Nigerian state ended up paying for energy in excess of what it can actually use. In a cat-and-mouse game, Azura has been threatening the Nigerian government to trigger the World Bank’s partial risk guarantee, a derisking instrument meant to discipline Nigeria into meeting its payment obligations to international investors. A triggered risk guarantee becomes a loan to Nigeria, as the de-risking state always pays, thus affecting its sovereign rating. As one Nigerian government official put it in 2024, “the agreement was a big mistake.” Lacking the resources to keep paying the exorbitant fees to Azura, he summarized that “this agreement is killing us.” Predictably, USAID celebrates the Azura deal quite simply as a “success.”

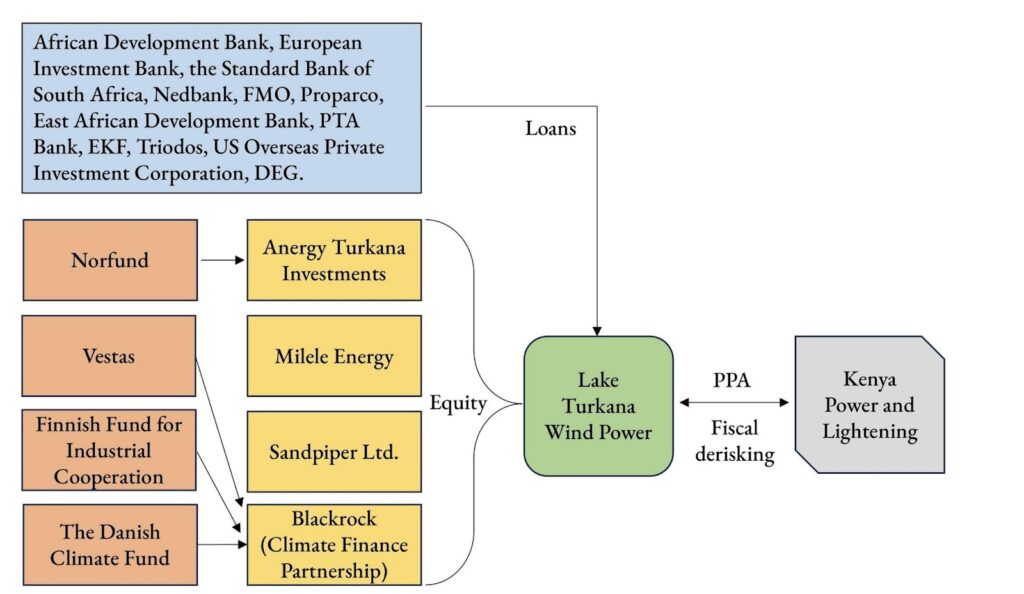

Another success story is the Lake Turkana Wind Power (LTWP) project. According to USAID, the agency “is creating an enabling environment for renewable power in Kenya by supporting a Grid Management program to help Kenya with grid management of intermittent renewables.” Private sector partners notably include Aldwych, working alongside the Standard Bank of South Africa, the African Development Bank and Nedbank committed financing and insurance, as well as the US Treasury Department.

The main equity owners included various Nordic public entities and Vestas, the Danish wind turbine manufacturer. These then sold their stakes to Anergy Turkana Investments, a state-owned South African asset manager, and Blackrock’s Climate Finance Fund. On the fiscal side, the Kenyan state entered a twenty-year power purchase agreement (PPA) that commits the state-owned Kenya Power and Lightening to purchasing the wind power generated. This fiscal derisking of demand was so generous to the LTWP owners that the World Bank withdrew its backing for the project; it stressed that the take-or-pay provision (like in the Azura case) would force the Kenyan state to pay for power it could not use. Even if the Kenyan grid could absorb it, the twenty-year contract locks Kenyan taxpayers into paying a Sh16/kWh price, now nearly three times higher than the Sh5.8/kWh market price. The Kipeto windfarm, now owned by the French asset manager Meridiam, is a similar take-or-pay arrangement, committing Kenya Power to compensate Meridiam in US dollars, thus taking currency risk from private investors.

The derisking extractivism became so controversial that in late 2024, a Kenyan parliamentary committee asked the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and the Directorate of Criminal Investigations to probe the role of state employees in the signing of the power purchase agreement between Kenya Power and LTWP. The Kenyan government ultimately imposed a moratorium on PPAs in the energy sector, but the implications of the agreement were not only fiscal. High energy costs undermine public efforts to strengthen the manufacturing capacity of the Kenyan economy and create new sources of political conflict between foreign-owned energy producers, the Kenyan state and local manufacturers.

USAID worked both as an instrument for humanitarian assistance and for extractivist derisking. In that domain, it placed emphasis on visible outcomes like infrastructure and investment while obscuring the long-term economic and social costs for those on the receiving end.

DOGE and foreign aid

This title of this piece is not my original turn of phrase. It hails from a blogpost by two Trumpist financiers: Jon Londsdale, a Peter Thiel mentee, and Ben Black. The latter, the son of Apollo Global Management co-founder Leon Black, was nominated by the Trump administration to head the DFC in its repurposed role as a more aggressive instrument of US economic power. As Bloomberg reports, the DFC would become Trump’s sovereign wealth fund, with its overall funding cap raised to $120 billion from its current $60 billion investment cap—already larger than USAID’s $40 billion budget.

A Harvard trained lawyer, Black heads the private equity firm Fortinbras, unironically named after Shakespeare’s character whom Hamlet describes as possessing “divine ambition,” his mark of greatness fighting for his family’s honor. The son of an asset stripper, he has now been tasked himself with stripping USAID of its commitments to humanitarian assistance—that’s what it means to DOGE.

Somewhat ironically, the two financiers’ diagnosis of USAID echoes that of Bernie Sanders, albeit while denouncing the politics that apparently drive it. Under Biden, they argue, USAID became a “dependency program for foreign nations,” an “absurd mission drift” wasting taxpayer money into virtue signaling projects like climate or gender equality, “pandering to the interest group-driven issue of the moment.” Alas, nothing on how USAID operations have been benefiting their tribe.

Instead, they propose to reorganize foreign aid with the purpose of “securing access to critical resources, building strong market economies, and promoting pathways for private capital to invest … backed by DFC financing, American mining, shipping, and resource-dependent businesses could step in, bringing capital and expertise” to strategic geopolitical interests like Greenland.

The DFC operations in 2023 offer a snapshot of its derisking activities. That year, it committed around $10 billion, $1.2 billion of which was earmarked for Ukraine, with no disclosed information on the specific programs. Its largest twenty investments are all over $100 million. The largest, totalling $747 million, committed to Gabon’s debt for nature swap. At first glance, such projects seem a win-win scenario: indebted nations like Gabon receive debt relief in exchange for commitments to environmental conservation. The problem, however, is that these swaps outsource environmental policy to external actors—in this case the US Nature Conservancy—and create profit opportunities for financiers—US Bank of America New York arranged the issuance of blue bonds. All the while, they do little to address the root causes of debt accumulation, such as exploitative trade relationships or volatile global financial markets.

Several of the DFC’s other large commitments illustrate its role at the intersection of US geopolitical priorities and US corporate interests. The DFC provided a $300 million guarantee to Goldman Sachs designed to underwrite potential derivative obligations arising from the company’s contract with PKN ORLEN, the Polish oil giant, as it sought to hedge its risks from imports of US liquefied natural gas. It committed $150 million to the private equity fund I Squared Climate Fund for infrastructure investments in India, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, El Salvador, Malaysia, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Peru, and Brazil. In another derisking operation, the DFC committed $100 million to private equity Global Access Fund, which privatizes water infrastructure via PPPs.

If the second Trump administration is chaotic in presentation, parts of its agenda are nonetheless coherent. The new government will turbocharge the extractivist derisking of USAID via the DFC—“feeding into the woodchipper,” as Elon Musk put it, the aid part of the US development agenda. It is the Wall Street Consensus on steroids, run by private equity titans for private equity.

Filed Under