Central banks are back in the spotlight. After more than three decades of low inflation in rich countries, the rise in prices observed between 2021 and 2023 forced academic discussions into the public sphere. Such debates are not restricted to technical economic issues but deal explicitly with the politics of central banking. In the recent case of the United States election, for instance, more than a few commentators pointed at inflation to explain Donald Trump’s victory. Some went further, arguing that inflation explains a general anti-incumbent bias in recent elections across the globe.

Economies south of the Equator were also subjected to the inflation wave, but their particular situation exposed different challenges faced by their inflation-targeting central banks. If the debates over monetary policy in the North have revealed to some degree the narrowness of interest rate policy in managing inflationary tensions, the particular constraints of Southern countries expose the limits of conventional monetary policy even more starkly. Placed below the rich economies in the currency hierarchy that structures the international monetary system, peripheral countries face distinct challenges—namely, vulnerability to global financial cycles and the difficulty of asserting monetary autonomy.

Many countries demonstrate this distinct position—think of recent controversies over monetary policy in Bolivia, Colombia or Turkey, each driven in part by the drying up of global liquidity. Brazil, with its extremely volatile currency, is a clear case of such challenges, but has been mired for two years in a public economic policy debate that largely fails to address the role of the global financial cycle. Instead, attention has been squarely focused on the levels of the interest rate set by the central bank. To be sure, Brazil’s extraordinarily high interest rates do have profound implications, and contribute to the reproduction of the country’s extreme inequalities. But the challenges posed by inflation require one to go beyond this immediate issue, and to seriously consider the question of capital controls.

Lula versus the central bank

When center-left Luís Inácio Lula da Silva started his third term as president in 2023, he was blocked from appointing the head of the Brazilian Central Bank and some of its directors by legislation approved during the far-right government of Jair Bolsonaro (2019–2022), his predecessor. Following international trends, Congress passed a law in 2021 to establish fixed terms for the central bank president and directors that do not align with the electoral cycle—the president of the central bank, for instance, now starts their term in office in the third year of the government that appointed him and outlives it for another two years.

The stated aim of the law was to prevent the politicization of monetary policy. But politicization could not be avoided through legislation. The president of the central bank appointed by Bolsonaro, Roberto Campos Neto, was not only loyal to him but was active in his campaign for reelection. (Among other things, Campos Neto allegedly created a polling aggregator to aid Bolsonaro’s campaign when he was already in charge of the central bank.) Less than three weeks into his third presidency, Lula started publicly blaming Campos Neto and high interest rates for blocking economic growth and job creation. Taking their cue, parts of the left and some critical economists declared Campos Neto the enemy. The latter, in turn, often resorted to monetary policy committee minutes to criticize government policies.1

There were abundant reasons for the complaints against the central bank, as it can be argued that it kept the interest rate at an excessively high level for an extended period, despite inflation slowing since mid-2022. Complaints may have been even more justified since April 2024, when Campos Neto made a series of public remarks that were read by some as an attempt to sabotage the government, pushing inflation expectations upward.

From the government’s perspective, the exchange of blows with Campos Neto served the political purpose of pulling focus away from Lula’s decision to not break decisively with austerity—its choice of a “slow-motion lulismo.”2 It also fostered hopes that, once Lula was allowed to replace Campos Neto in 2025, monetary policy could shift to an expansionary stance, contributing to push the economy forward. But when 2025 arrived, the situation had changed, and the earlier hopes were all but shattered.

Lula’s appointee to head the central bank is Gabriel Galípolo, a young former banker who has also traveled in left-wing economics circles.3 After a brief period working at Lula’s Ministry of Finance, Galípolo was nominated for the board of the central bank in mid-2023. During the first seven monetary policy committee meetings he took part in, the board lowered the interest rate.4 But in a subsequent set of six meetings, Galípolo backed a pause in monetary policy easing (in the first two) and then its reversal (in the last four)—rates have risen so far from 10.5 to 13.25 percent. In the most recent meeting, the first since Galípolo was made President, the rate was hiked 1 percentage point.

Meanwhile, some economists on the left—acknowledging that Campos Neto’s exit would not bring with it lower interest rates—have shifted their target. In an open letter addressed to the National Monetary Council, nine influential critical economists argued that price rigidities and indexation prevalent in the Brazilian economy make the current inflation target (of 3 percent) “dysfunctional,” calling for a change of the target to 4 percent to “allow for a more balanced growth of the Brazilian economy.” Since then, others have joined the chorus.5

The Brazilian inflation target remained 4.5 percent between 2005 and 2018 and, since 2019, has been lowered 0.25 percentage points each year—in keeping with the disinhibited neoliberalism that characterized Brazilian economic policy after the Workers’ Party (PT) was ousted from power in 2016. Lula himself broached the possibility of increasing the target in 2023, during his disagreements with Campos Neto, but the government has so far opted to keep it at 3 percent.

What happened? Why wasn’t Campos Neto’s exit sufficient to ease the central bank’s stance? Why has Galípolo backed the recent increases in interest rates, including the aggressive hikes of one percentage point decided upon during the last two committee meetings?

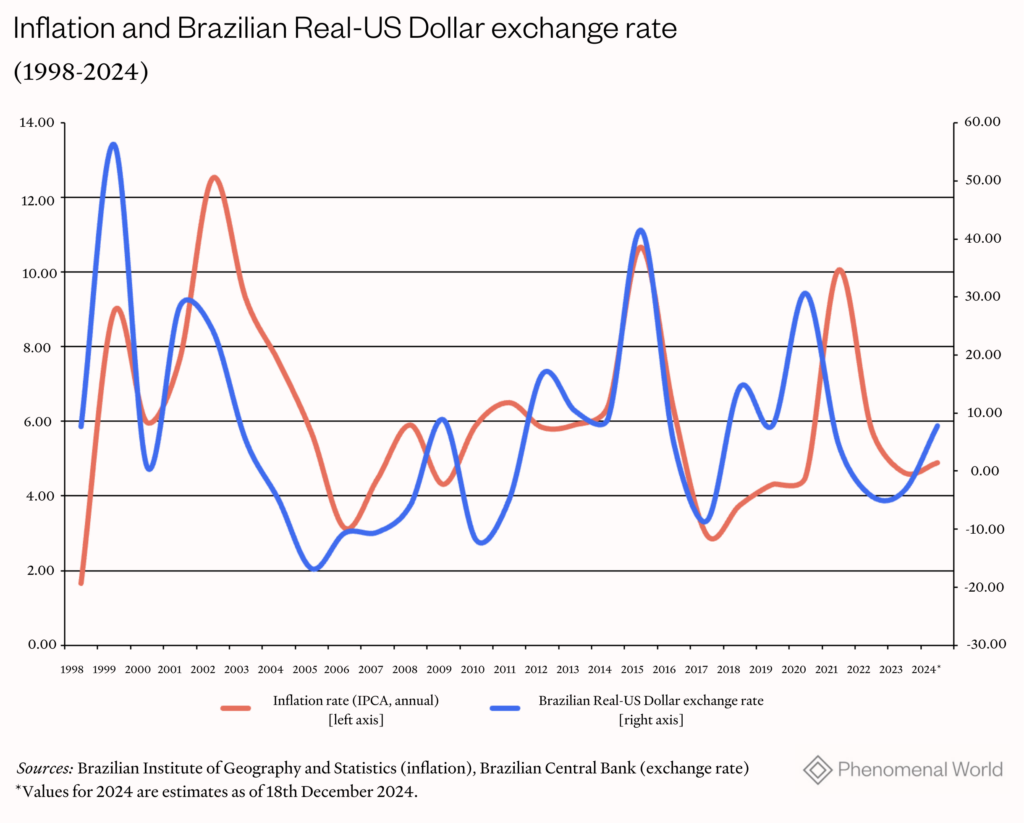

The answer lies in the trajectory of inflation itself. After peaking at 12.1 percent in April 2022 as part of the global pandemic inflation wave, it declined sharply to 3.2 by June 2023. Since then, however, inflation increased again and closed 2024 at 4.8 percent—higher than the 4.5 percent threshold set by the inflation targeting regime, which admits a 1.5 deviation from the target. Unsurprisingly, conventional economists blame fiscal policy uncertainties for both the recent currency depreciation and the rise of inflation, and call for their preferred solution of austerity. Telling as it is of the underlying political disputes, this much-abused argument fails to explain the latest macroeconomic turmoil.

Global financial cycles

It is perhaps the curse of large countries to be inward-looking, registering all developments as domestically determined. This tendency has not escaped foreign observers: historian Perry Anderson, for instance, argued that Brazilian national culture is “uniquely self-contained.” Macroeconomic policy debates are not an exception to this rule. Sometimes honestly, other times in bad faith, they underestimate the role of the global financial cycles in exchange rate movements and, consequently, inflation rates.

The one variable that remains the most crucial determinant of changes in the price level in Brazil is the exchange rate, as illustrated below, which not only impacts the price of imports and domestically produced tradable goods but also some service prices like rents, which are usually readjusted based on an index that closely tracks currency movements. The exchange rate, in turn, moves in tandem with those of most peripheral countries—even if its oscillations tend to be stronger than the average—reacting to global fluctuations of liquidity that are determined by the United States’ monetary policy.6 To understand Brazilian inflation, one needs to examine global financial cycles.

Inflation targeting was established in Brazil in 1999, replacing the currency anchor as the primary stabilization tool amidst the global shocks of the late 1990s. According to one periodization, the period from 1997 to 1999 was marked by a double bust: the coincidence of cyclical declines of capital flows and commodity prices. The Brazilian economy had managed to overcome persistent hyperinflation in 1995 by pegging its currency to the US dollar, in the run-up to the double bust. But despite its efforts to attract foreign capital to sustain the peg—the basic interest rate averaged 23.7 percent between 1996 and 1998—the volatility of capital flows that wreaked havoc in Mexico, East Asia, and Russia in those years eventually forced the Brazilian real to float.

Following the global trend, Brazil replaced its fixed exchange rate regime with inflation targeting and succeeded in preserving some degree of stability, but at a very high cost (unemployment and inequality increased, and foreign debt levels soared, with the basic interest rate being set at 45 percent in 1999). Having declined from 9.6 to 1.7 percent between 1996 and 1998, inflation jumped back up to 8.9 in 1999, due to the large depreciation, but then averaged 6.8 in the following two years. Subsequently, uncertainties related to the Nasdaq crisis in the US combined with domestic electoral speculation in 2001 and 2002, forced further devaluations of the real of 25 percent each year, in turn pushing inflation back up to 12.5 percent.

As Lula entered office for the first time in January 2003, the double bust had transformed into a double boom. The reordering of the global economy with China’s integration into world production and trade circuits resulted in a decade of growth acceleration, increasing commodity prices, and a capital flow bonanza, which lasted until 2011. Gradually but steadily, the exchange rate appreciated from the peak of 3.89 reais per dollar in September 2002 to the trough of 1.56 in July 2011. Inflation, in turn, was kept within the target band between 2004 and 2014, averaging 5.4 percent annually until 2011—while the double boom lasted. And, finally, the basic interest rate was allowed to come down from 19.8 to 14.5 percent—comparing the averages for 1999–2002 and 2003–2011, respectively.

Politically, the government took advantage of this period to adopt policies that substantially reduced wage inequality and boosted domestic demand. At the same time, property income flowing to the top became increasingly concentrated, while the double boom stimulated rising household indebtedness. The trend was regional: accelerating growth with falling wage inequality was the common characteristic of the so-called Pink Tide countries. But the promising trajectory of inclusive growth had a less appealing counterparty, as the boom consolidated the region as an exporter of primary commodities, increased the external vulnerabilities of its economies, and empowered an extractivist and agrarian fraction of the ruling class that would eventually draw the Pink Tide to a close and weaken the countries’ young democratic institutions.

In 2011, as the double boom became once again a double bust, difficulties started to emerge. In Brazil, the exchange rate depreciated à la Hemingway—gradually and then suddenly—peaking at 4 reais per dollar in January 2016. Inflation followed suit: it averaged 6.1 between 2012 and 2014, despite great effort by the government to keep administered prices in check, then jumped to 10.7 in 2015. The central bank’s sharp contractionary turn, increasing the basic rate from 7.25 to 14.25 percent, between April 2013 and July 2015, had a limited effect: the pressures on the price level and on the currency would only ease from 2016 onwards, when global conditions turned again, and global liquidity started to recover.

2016 was also the year in which the PT was ousted from government by a parliamentary coup. The subsequent governments took a series of measures to dismantle redistributive mechanisms, including labor market and pension reforms and a constitutional freeze on government spending. The resulting combination of stagnation and a relatively stable exchange rate kept inflation at a low level, until the pandemic struck. When it did, capital outflows from the periphery were vertiginous, with the Brazilian exchange rate depreciating around 30 percent in 2020 alone and inflation reaching a peak at 12.1 percent.

The point is not that domestic determinants do not matter for inflation dynamics in Brazil; the way that the global financial cycle impacts the economy is shaped both by its structural position within the world economy and by its domestic policy decisions. But peripheral economies are regularly overwhelmed by sudden movements of global financial flows, which force their governments to face stark trade-offs.

When capital flows out, economic activity is usually driven down, while prices are driven up. In this circumstance, the government can raise the interest rate to manage inflation, via the impact of the interest rate on capital flows and the exchange rate, thereby feeding the contraction. The government’s other option is to let inflation squeeze purchasing power, hoping that exports stimulated by the depreciated currency will compensate for diminished domestic demand and preserve employment. The more open to capital flows an economy is, the more acute the trade-off. Richer economies at the center, with stronger currencies, face significantly milder dilemmas, as the pass-through from exchange rate movements to prices tends to be much smaller.

The pendulum

Why would economies open themselves to capital flows, then? Foreign capital tends to be represented as a necessary tool to jumpstart development, investing in activities beyond the reach of domestic agents and bringing with it new technology and advanced management practices. But these benefits tend to be elusive: even in the form of productive investment—that is, a multinational corporation opening a plant—capital inflows often risk creating enclaves, weakly connected to the rest of the economy, focused on repatriating profits out of the recipient country.

The bulk of capital flows is not represented by productive investments, but by short-term portfolio flows seeking the largest gains on the shortest time horizon. These hot money flows, as they are aptly called, tend to burn receiving countries.

Understandably, then, the regulation of capital flows has historically been a contested issue, following the double movement described by Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation. When financiers push for financial liberalization, a countermovement reacts to protect society from the resulting volatility. In the era of the gold standard, examined by Polanyi, unregulated capital flows were one of the three drivers of the satanic mill that sowed the seeds for the world wars and the rise of fascism. Describing its consequences in the late 1920s, he wrote:

“An almost unbroken sequence of currency crises linked the indigent Balkans with the affluent United States through the elastic band of an international credit system … ‘Flight of capital’ was a new thing. … And yet, its vital role in the overthrow of the liberal governments of France in 1925, and again in 1938, as well as in the development of a fascist movement in Germany in 1930, was patent.”

Amid the debris of World War II, the pendulum swung. At the Bretton Woods conference, the planners of the postwar order agreed that governments had the right to control “all capital movements.” To one of its architects, John Maynard Keynes, the shift was clear: “what used to be heresy,” he said, “is now endorsed as orthodoxy.”7 The new vision lasted many decades, during which free capital flows were the exception, rather than the rule. Almost half a century later, in 1989, John Williamson—in his codification of the Washington Consensus—shied away from an open call for complete liberalization, focusing only on foreign direct investment. “Liberalization of foreign financial flows,” he wrote, “is not regarded as a high priority. In contrast, a restrictive attitude limiting the entry of foreign direct investment is regarded as foolish.”8

But after decades of deepening global economic integration, with production increasingly fragmented in transnational supply chains welded together by haute finance, the forces pushing for liberalization were eventually ready to strike back. In 1997, Michel Camdessus, then Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, proposed to amend the articles of agreement of the Fund to allow the institution to officially push for financial liberalization. The consequences of the double bust, in particular the East Asian crisis, stood in the way of the intended amendment, which was never approved.9 But the tide toward liberalization was already in motion. As Dani Rodrik recalled, despite the failure to amend its statutes, “the IMF continued to goad countries it dealt with to remove domestic impediments to international finance, and the United States pushed its partners in trade agreements to renounce capital controls.”10

Brazil, alongside its Latin American neighbors, heeded the call early on. In the 1990s, a social bloc defending neoliberal reforms started to coalesce and the first laws to dismantle capital controls and liberalize the foreign exchange markets were enacted. This was the force that sustained the currency peg and slayed hyperinflation of the 1990s. Once Lula became president, in 2003, liberal economists argued that price stabilization would only be consolidated if financial liberalization went all the way, making the real “fully convertible.” In opposition, economists on the left summoned theoretical and empirical arguments to claim that further liberalization would only push the Brazilian currency further down the global hierarchy, deepening external vulnerability. But their arguments did not prevail. Slowly but unambiguously, policy moved in the direction of deeper convertibility—the Polanyian pendulum was again in full swing.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, the first cracks in the consensus toward financial liberalization started to show. In Brazil, Dilma Rousseff decided to shift economic policy to mitigate the negative impacts of the overvalued real on manufacturing production. The currency had hit bottom in July 2011, six months into her term in office. A series of measures were adopted to reduce currency volatility and manage capital flows, including selective taxation of—and the imposition of reserve requirements on—different foreign exchange operations, including currency derivatives. For a time, these measures were effective in increasing exchange rate stability. In 2012, Rousseff’s finance minister claimed that Brazil was prepared to face a global “monetary tsunami,” dramatically comparing the situation to the disaster that had struck Fukushima a year earlier. Politically, however, the government was not prepared—it moved to discipline finance without having forged a coalition capable of withstanding the reaction. As global liquidity dried out, pressure mounted to restore the neoliberal policy framework and adopt monetary and fiscal austerity. In 2013, capital controls were abandoned.

Globally, however, the shift toward capital controls went ahead. In 2012, the IMF issued an “institutional view” on the topic, stating in its characteristically cautious language that “there is … no presumption that full liberalization is an appropriate goal for all countries at all times … In certain circumstances, capital flow management measures can be useful.” The following year, at the world’s central bankers’ rendezvous in Jackson Hole, economist Hélène Rey went further. Given that “gross capital inflows, leverage, credit growth, and asset prices dance largely to the same tune,” she claimed that the standard view, which maintained that countries had autonomy to set their monetary policies in the presence of financial liberalization, was an illusion: “Independent monetary policies are possible if and only if the capital account is managed.”11

A few years later, in 2016, IMF economists once again put capital controls in the spotlight, highlighting it alongside two other policies in a self-critical article titled “Neoliberalism: oversold?” They claimed that “capital controls are a viable, and sometimes the only, option” available to countries facing “an unsustainable credit boom.” Finally, in 2020, reacting to the disastrous capital outflows from the global periphery as investors sought security in the first months of the pandemic, the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office argued that the fund’s “institutional view” on the topic should be revised, “allowing for … more long-lasting use of capital flow measures.”

Brazil, however, kept swimming against the tide, still trapped in the previous consensus—due to the extraordinary role played by financial interests in its political economy. During Bolsonaro’s government, as part of its request to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a law that further liberalized currency markets was enacted to comply with the organization’s rules. But with its extreme currency volatility, the Brazilian economy is particularly subject to global financial cycles. If the political strength of high finance over economic policy goes unchallenged, the country will remain atop the rankings of external vulnerability.

Market discipline and democratic risk

At stake is not only economic stability, but also the survival of democratic institutions. In the interwar period, examining Europe, Polanyi remarked: “Labour Parties were made to quit office ‘to save the currency’” or “in the name of sound monetary standards.”12 Almost a century later, the authoritarian threat has not been put to rest.

During Lula’s first successful presidential campaign, in 2002, currency speculation and the threat of capital flight were so intense—the financial media both named and perpetuated a fear of the “Lula risk”—that he issued a letter committing to abide by the neoliberal policy framework. Taking stock of the episode, scholar Daniela Campello concluded: “There is no way to understand either the Lula presidency or its consequences to the Brazilian Left without reference to financial globalization and market discipline.” Halfway through his third term as president, such pressures remain.

Last November, the Ministry of Finance announced a fiscal plan that cut back some social transfers and slowed down minimum wage increases in an attempt to convince the “markets” of its commitment to eliminating the fiscal primary deficit. It also included a proposal to extend income tax exemptions to parts of the middle classes, compensating it with an increase in taxes on the rich. Economists from financial institutions took it personally, touting their resistance to progressive taxation under the pretense of fiscal responsibility.

In two days, the real lost almost 4 percent of its value against the dollar, and three weeks later depreciation had reached 6 percent, effectively pushing inflation above the target band. Interviewed by the Financial Times, one portfolio manager pleaded guilty: “The market is very concerned regarding Brazil’s fiscal accounts and especially the government’s response to it. The only way the market has to call the attention of the government is through the exchange rate.”

Despite his recent fall in popularity, Lula’s government may opt to keep at its current strategy, taking great pains to avoid stirring conflict and hoping a divided opposition keeps open the path to reelection. To its loyal base in the poorest sections of Brazilian society, the PT offers to mitigate the harshest edges of Brazil’s inherited austerity, as well as some reforms to make the tax system more progressive. The increased budget that Lula negotiated before taking office has so far kept growth going at a somewhat high rate, in comparison with the quasi-stagnation of the past decade, but its lagged effects are bound to be reduced in the final two years of his term. With conservative parties recently strengthened by municipal elections and the far-right emboldened by Trump’s electoral success, the risks involved in staying the course are high. And with the new US government aggressively attacking trade globalization, more likely than not the next two years will be characterized by global financial turbulence, with its usual impacts on peripheral currencies.

An alternative path would entail shifting the country’s economy in a direction that can reduce its external vulnerability and, at the same time, its reliance on the agrarian elites—increasingly loyal to the far-right—in order to forge a social bloc that stands a better chance of holding the authoritarian threat at bay. Catching up with the global trend of reversing financial liberalization would be particularly useful in this regard. It could not only attenuate the impact of the global financial cycle on the Brazilian economy but also weaken the financial capitalists’ blackmailing tool over government policy.

For this purpose, the experience of managing capital flows in 2011 and 2012 may be particularly useful, suggesting a series of potentially effective instruments—from reserve requirements on different currency operations (especially derivatives) to selective taxation targeting short-term flows—all of them under the control of the government.13 As financial institutions are prone to continuously devise new instruments and operations to escape the constraints of regulation, targeting would need to be regularly revised in light of detailed assessments of market dynamics. But the rationale should be clear from the outset: focusing on hot money and carry-trade operations in order to avoid impacting longer-term flows and placing excessive pressure on the balance of payments.

Any step in that direction would certainly create animosity with financial institutions, which would stand to lose the profits they accrue from short-term financial speculation. However, as the latest currency turmoil indicates, a strong contingent among the financial elites places itself in opposition anyway, being determined to push the government to commit to deepening austerity. Challenging them is unavoidable for Lula if he is to even partially fulfill his electoral promises or avert the far-right’s return to power. By focusing on capital controls, the government could empower itself to weather the challenges posed by global financial cycles and enable long-term strategies to overcome the productive bases of external vulnerability—a strategy that would in this case be better protected against global turbulence and domestic financial opposition.

FootnotesSee A. C. Costa (2023). “Fernando Haddad, a ascensão,” Revista Piauí, for a detailed account of the struggle between the government and the central bank in the period.

For an assessment of Lula’s government’s fiscal policy, see A. Singer and F. Rugitsky, “Slow motion lulismo,” Sidecar – New Left Review, January 2024.

While Galípolo was serving as CEO of financial firm Banco Fator, he co-authored with prominent left-wing economist Luiz Gonzaga Belluzzo some books on economics in the Marxian tradition, including, for example, Dinheiro: o poder da abstração real (Money: the power of real abstraction), Editora Contracorrente, 2019.

In the first one, in August 2023, Galípolo’s vote was decisive to lower the rate by 0.5 percentage points, defeating four members of the committee who voted for a decline of 0.25. In the meeting in May 2024, however, he was on the defeated side, voting for a further decline of 0.5 as the majority, including Campos Neto, opted for a decline of 0.25. The explicit disagreement between the two was used then by economists from financial institutions to spread concerns about Galípolo and the risk of monetary policy losing credibility were he to become the president of the central bank. He promptly reacted, praising Campos Neto, in an attempt to reassure the markets. Unanimity in the monetary policy committee was soon restored.

For different reasons, conventional economists like Olivier Blanchard have also called for a higher inflation target for rich economies.

According to a recent calculation by Rodrigo Toneto with data from the Bank of International Settlements, the real was the most volatile of 15 different currencies between 2001 and 2019—a sample including famously turbulent economies, like the Argentinian one. Pedro Rossi argued that the extreme volatility of the Brazilian currency can be partly attributed to the fact that the derivatives market is more liquid than the spot market in the country.

Quoted by Dani Rodrik in The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy (New York and London: W.W. Norton, 2011).

John Williamson, “What Washington Means by Policy Reform,” in Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened? Edited by John Williamson (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 1993)

The episode was registered by Frank Veneroso and Robert Wade in their article, “The gathering world slump and the battle over capital controls,” New Left Review, 1998.

Dani Rodrik, 2011.

Hélène Rey, “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence,” Working Paper No. 21162, National Bureau of Economic Research, May, 2015

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (New York: Farrar & Rineaus, 1944)

In Brazil, these tax instruments are referred to as IOF (imposto sobre operações financeiras, tax on financial transactions).

Filed Under